Theses on Sleep

created: ; modified:2024 update: Please note that as of 2024, I aim to sleep 7-8 hours most of the nights.

Summary: In this essay, I question some of the consensus beliefs about sleep, such as the need for at least 7 hours of sleep for adults, harmfulness of acute sleep deprivation, and harmfulness of long-term sleep deprivation and our inability to adapt to it.

It appears that the evidence for all of these beliefs is much weaker than sleep scientists and public health experts want us to believe. In particular, I conclude that it’s plausible that at least acute sleep deprivation is not only not harmful but beneficial in some contexts and that it’s that we are able to adapt to long-term sleep deprivation.

I also discuss the bidirectional relationship of sleep and mania/depression and the costs of unnecessary sleep, noting that sleeping 1.5 hours per day less results in gaining more than a month of wakefulness per year, every year.

Note: I sleep the normal 7-9 hours if I don’t restrict my sleep. However, stimulants like coffee, modafinil, and adderall seem to have much smaller effect on my cognition than on cognition of most people I know. My brain in general, as you might guess from reading this site, is not very normal. So, be cautious before trying anything with your sleep on the basis of the arguments I lay out below. Specifically do not make any drastic changes to your sleep schedule on the basis of reading this essay and, if you want to experiment with sleep, do it gradually (i.e. varying the average amount of sleep by no more than 30 minutes at a time) and carefully.

Also see Natália Coelho Mendonça Counter-theses on Sleep.

Comfortable modern sleep is an unnatural superstimulus. Sleepiness, just like hunger, is normal.

The default argument for sleeping 7-9 hours a night is that this is the amount of sleep most of us get “naturally” when we sleep without using alarms. In this section, I argue against this line of reasoning, using the following analogy:

- Experiencing hunger is normal and does not necessarily imply that you are not eating enough. Never being hungry means you are probably eating too much.

- Experiencing sleepiness is normal and does not necessarily imply that you are undersleeping. Never being sleepy means you are probably sleeping too much.

Most of us (myself included) eat a lot of junk food and candy if we don’t restrict ourselves. Does this mean that lots of junk food and candy is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount for health?

Obviously, no. Modern junk food and candy are unnatural superstimuli, much tastier and much more abundant than any natural food, so they end up overwhelming our brains with pleasure, especially given that we are bored at work, college, or in high school so much of the day.

What if the only food available to you was junk food and candy?

- If you don’t eat any, you starve.

- If you eat just enough to be lean, you’ll keep salivating at the sight of pizzas and ice cream and feel distracted and hungry all the time. Importantly, in this situation, the feeling of hunger does not mean that you should eat more – it’s your brain being overpowered by a superstimulus while being bored.

- If you eat it as much as you want, you’ll probably eat too much and become fat.

- And if you eat way too much candy or pizza at once, you’ll be feeling terrible afterwards, however tasty the food was.

Most of us (myself included) sleep 7-9 hours if we don’t have any alarms in the morning and if we get out of bed when we feel like it. Does this mean that 7-9 hours of sleep is the “natural” or the “optimal” amount?

My thesis is: obviously, no. Modern sleep, in its infinite comfort, is an unnatural superstimulus that overwhelms our brains with pleasure and comfort (note: I’m not saying that it’s bad, simply that being in bed today is much more pleasurable than being in “bed” in the past.)

Think about sleep 10,000 years ago. You sleep in a cave, in a hut, or under the sky, with predators and enemy tribes roaming around. You are on a wooden floor, on an animal’s skin, or on the ground. The temperature will probably drop 5-10°C overnight, meaning that if you were comfortable when you were falling asleep, you are going to be freezing when you wake up. Finally, there’s moon shining right at you and all kinds of sounds coming from the forest around you.

In contrast, today: you sleep on your super-comfortable machine-crafted foam of the exact right firmness for you. You are completely safe in your home, protected by thick walls and doors. Your room’s temperature stays roughly constant, ensuring that you stay warm and comfy throughout the night. Finally, you are in a light and sound-insulated environment of your house. And if there’s any kind of disturbance you have eye masks and earplugs.

Does this sound “natural”?

Now, what if the only sleep available to you was modern sleep?

- If you don’t sleep at all, you go crazy, because some amount of sleep is necessary.

- If you sleep just enough to be awake during the day, you’ll be dreaming of getting a nap at the sight of a bed and will be distracted and sleepy all the time. Importantly, I claim, in this situation, the feeling of sleepiness does not mean that you should sleep more – it’s your brain being overpowered by a superstimulus while being bored.

- I claim that if you sleep as much as you want, you’ll probably sleep too much and become more susceptible to depression.

- And if you sleep way too much at once, you’ll be feeling terrible afterwards, however pleasant the sleep was.

Even if I convinced you about the “sleeping too much” part, you are still probably wondering: but what does depression have to do with anything? Isn’t sleeping a lot good for mental health? Well…

Depression <-> oversleeping. Mania <-> acute sleep deprivation

In this section, I argue that depression triggers/amplifies oversleeping while oversleeping triggers/amplifies depression. Similarly, mania triggers/amplifies acute sleep deprivation while acute sleep deprivation triggers/amplifies mania.

One of the most notable facts about sleep is just how interlinked excessive sleep is with depression and how interlinked sleep deprivation is with mania in bipolar people.

Someone in r/BipolarReddit asked: How many hours do you sleep when stable vs (hypo)manic? Depressed?

Here are all 8 answers that compare hours for manic and depressed states, I excluded answers that describe hypomania but do not describe mania or that only describe mania or only describe depression. note the consistency:

- “Manic/hypomanic: 0-6 hours Stable: 7-9 hours Depressed: 10-19 hours”

- “Manic, 2-3, hypo, 5-6, stable 8-9, depressed 10-12. 8 is the number I try to hit.”

- “Severely depressed w/o mixed features - 12 to 15 hours

Low to Moderate depressed w/o mixed - 10 hours, if no alarm. With alarm less, but super hangover

Stable -Usually 7-9 hours

Hypomanic taking sedating evening meds - 5 to 7 hours

Hypomanic with no sedating evening meds - 3 to 5 hours

Manic out of hand - 0 to 3 hours

Manic in hospital put on maximum sedating meds or injections - 4 to 6 hours

Mixed episodes = same as hypo(manic)” - “I try to get at least 8 hours but when I’m depressed I nap a lot. When I’m hypo I sleep pretty much the same but when I’m manic I’m lucky to get 3 hours. Huhs”

- “Just got out of a manic episode. A few all-nighters, a lot of 3 hour nights, and a good night of sleep was 6 hours. Now I’m depressed and I’ve been sleeping from 9pm to noon and staying in bed for much longer after I’m awake.”

- “Manic 2-4, stable 6-7, depressed 10-12”

- “Around 15 hours of sleep per night while depressed, and between 0-4 hours per night while manic.”

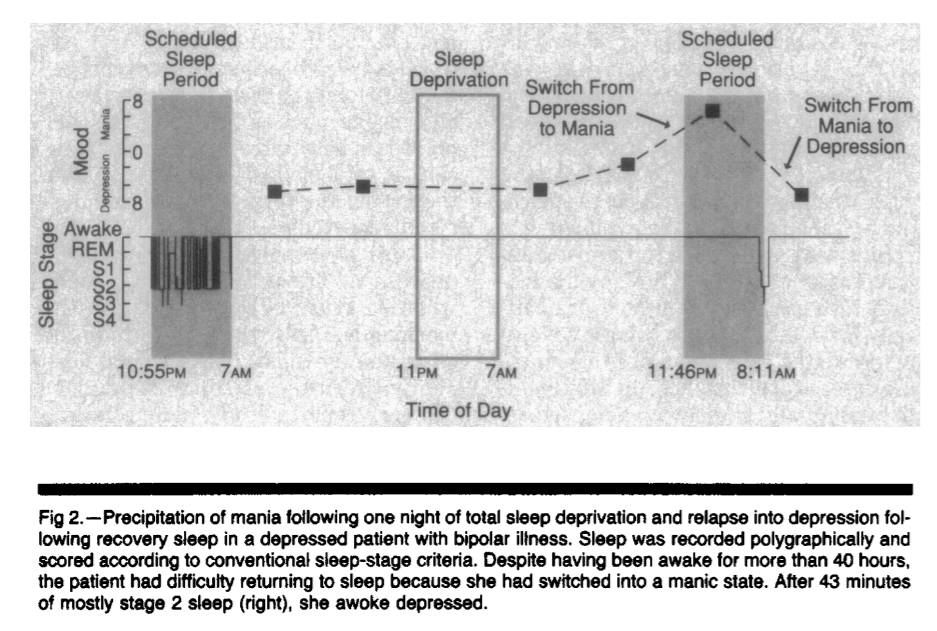

Lack of sleep is such a potent trigger for mania that acute sleep deprivation is literally used to treat depression. Aside from ketamine, not sleeping for a night is the only medicine we have to quickly – literally overnight – and reliably (in ~50% of patients) improve mood in depressed patients (until they go to bed, unless you keep advancing their sleep phase Riemann, D., König, A., Hohagen, F., Kiemen, A., Voderholzer, U., Backhaus, J., Bunz, J., Wesiack, B., Hermle, L. and Berger, M., 1999. How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 249(5), pp.231-237. ). NOTE: DO NOT TRY THIS IF YOU ARE BIPOLAR, YOU MIGHT GET A MANIC EPISODE.

Figure 1. Copied from Wehr TA. Improvement of depression and triggering of mania by sleep deprivation. JAMA. 1992 Jan 22;267(4):548-51.

Why does the lack of sleep promote manic states while long sleep promotes depression? I don’t know. But here are a couple of pointers to interesting papers relevant to the question: Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic? Beersma DG, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic?. Journal of affective disorders. 1992 Feb 1;24(2):101-8. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is associated with synapse growth. Sleep deprivation appears to increase BDNF [and therefore neurogenesis?]. Papers that showed up when I googled “sleep deprivation bdnf”: The Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor: Missing Link Between Sleep Deprivation, Insomnia, and Depression. Rahmani M, Rahmani F, Rezaei N. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor: missing link between sleep deprivation, insomnia, and depression. Neurochemical research. 2020 Feb;45(2):221-31. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. Eckert A, Karen S, Beck J, Brand S, Hemmeter U, Hatzinger M, Holsboer-Trachsler E. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. European Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;41(S1):S282-. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Giese M, Unternährer E, Hüttig H, Beck J, Brand S, Calabrese P, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Eckert A. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Molecular psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):151-2. Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation. Goldschmied JR, Rao H, Dinges D, Goel N, Detre JA, Basner M, Sheline YI, Thase ME, Gehrman PR. 0886 Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation. Sleep. 2019 Apr;42(Supplement_1):A356-.

Jeremy Hadfield writes:

My (summarized/simplified) hypothesis based on what I’ve read: depression involves rigid, non-flexible brain states that correspond to rigid depressive world models. Depression also involves a non-updating of models or inability to draw new connections (brain is even literally slightly lighter in depressed patients). Sleep involves revising/simplifying world models based on connections learned during the day, involves pruning unneeded or irrelevant synaptic connections. Thus, excessive sleep + depression = even less world model updating, even more rigid brain, even fewer new connections. Sleep deprivation can resolve this problem at least temporarily by ensuring that you stay awake for longer and keep adding connections, thus compensating for the decreased connection-building caused by depression and “forcing” a brain update (perhaps through neural annealing - see QRI article).

Occasional acute sleep deprivation is good for health and promotes more efficient sleep

One other argument for sleeping the “natural” (7-9) number of hours is that we feel bad on days when we sleep less. In this section, I argue against this line of reasoning by asking: if fasting and exercising are good, shouldn’t acute sleep deprivation also be good? And I conclude that it is probably good.

Let’s continue our analogy of sleep to eating and add exercise to the mix.

It seems to me that most common arguments against acute sleep deprivation equally “demonstrate” that fasting and exercise are bad.

For example, I ran 7 kilometers 2 days ago and my legs still hurt like hell and I can’t run at all. Does this mean that running is “bad”?

Well, consensus seems to be that dizziness, muscle damage (and thus pain) and decreased physical performance after the run, are not just not bad, but are in fact necessary for the organism to train to run faster or to run longer distances by increasing muscle mass, muscle efficiency, and lung capacity.

What about fasting? When I fast, I am more anxious, I think about food a lot, meaning that focus is more difficult, and I feel cold. And if I decided to fast too much, I would pass out and then die. Does this mean that fasting is “bad”? Well, consensus seems to be that occasional fasting actually activates some “good” kind of stress, promotes healthy autophagy, (obviously) helps to lose weight, etc. and is in fact good.

Now, what happens when I sleep for 2 hours instead of 7 one night? I feel somewhat tingly in my hands, my mood is heightened a little bit, and, if I start watching a movie with my wife at 6pm, I’ll fall asleep. Does this mean that sleeping 2 hours one night is bad for my health?

Obviously no. The only thing we observe is that my organism was subjected to acute stress. However, the reaction to acute stress does not tell us anything about the long-term effects of this kind of stress. As we know, both in running and in fasting, short-term acute stress response results in adaptation and in long-term increase in performance and in benefit to the organism.

I combed through a lot of sleep literature and I haven’t seen a single study that made a parallel to either fasting or exercise and I haven’t seen a single pre-registered RCT that tried to see what happens to someone if you subject them to 1-3 nights per week of acute sleep deprivation and allow to recover the rest of the nights. Do they perform better or worse in the long-term on cognitive tests? Do they have more or less inflammation? Do they need less recovery sleep over time?

I think that the answers are:

- Acute sleep deprivation combined with caffeine or some other stimulant that cancels out sleep pressure does not result in decreased cognitive ability at least until 30-40 hours of wakefulness (if this is true, then sleepiness, rather absence of sleep per se is responsible for decreased cognitive performance during acute sleep deprivation).

- Occasional acute sleep deprivation has no impact on long-term cognitive ability or health.

- Sleep does become more efficient over time and, in complete analogy to exercise, you withstand both acute sleep deprivation better and can function at baseline with a lower amount of sleep in the long-term.

(The only parallel to fasting I’m aware of anyone making is by Nassim Taleb… when he was quote-tweeting me.)

Also see:

- Appendix: anecdotes about acute sleep deprivation

- Appendix: Philipp Streicher on homeostasis, its relationship to mania/depression, and on other points I make

Our priors about sleep research should be weak

In this section, I note that most sleep research is extremely unreliable and we shouldn’t conclude much on the basis of it.

Do you believe in power-posing? In ego depletion? In hungry judges and brain training?

If the answer is no, then your priors for our knowledge about sleep should be weak because “sleep science” is mostly just rebranded cognitive psychology, with the vast majority of it being small-n, not pre-registered, p-hacked experiments.

I have been able to find exactly one pre-registered experiment of the impact of prolonged sleep deprivation on cognition. It was published by economists from Harvard and MIT in 2021 and its pre-registered analysis found null or negative effects of sleep on all primary outcomes Bessone P, Rao G, Schilbach F, Schofield H, Toma M. The economic consequences of increasing sleep among the urban poor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2021 Aug;136(3):1887-941. (note that both the abstract and the main body of this paper report results without the multiple-hypothesis correction, in contradiction to the pre-registration plan of the study. The paper does not mention this change anywhere. See comments for the details. ).

So why has sleep research not been facing a severe replication crisis, similar to psychology?

First, compared to psychology, where you just have people fill out questionnaires, sleep research is slow, relatively expensive, and requires specialized equipment (e.g. EEG, actigraphs). So skeptical outsiders go for easier targets (like social psychology) while the insiders keep doing the same shoddy experiments because they need to keep their careers going somehow.

Second, imagine if sleep researchers had conclusively shown that sleep is not important for memory, health, etc. – would they get any funding? No. Their jobs are literally predicated on convincing the NIH and other grantmakers that sleep is important. As Patrick McKenzie notes, “If you want a problem solved make it someone’s project. If you want it managed make it someone’s job.”

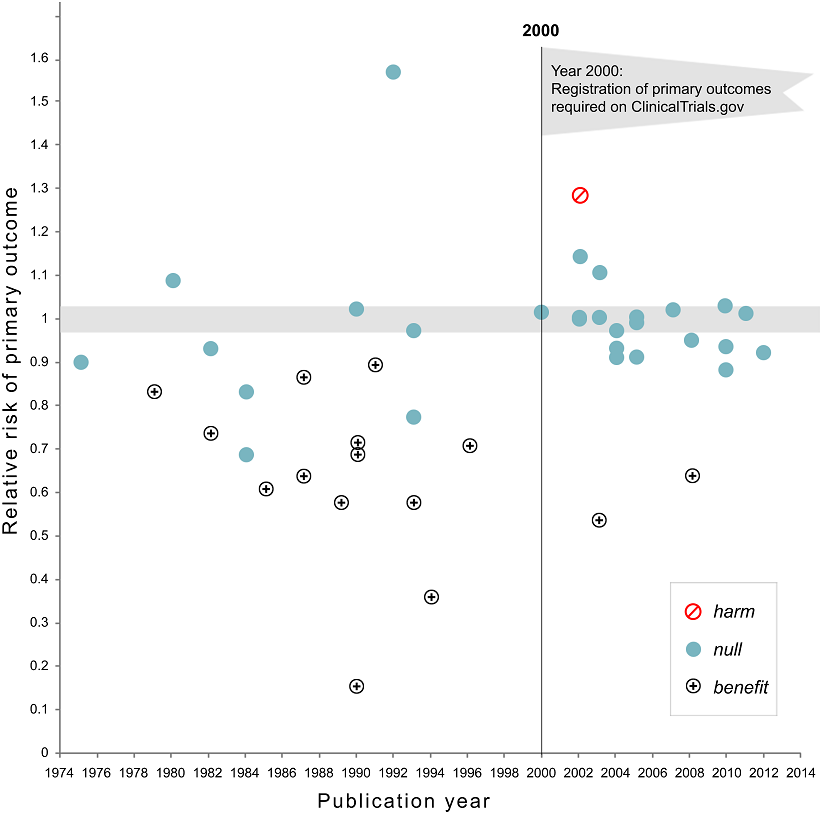

Figure 2. Relative risk of showing benefit or harm of treatment by year of publication for large NHLBI trials on pharmaceutical and dietary supplement interventions. Copied from Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382.

Figure 3. Eric Turner on Twitter: “Negative depression trials…Now you see ’em, now you don’t. Published literature vs FDA, from [Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 17;358(3):252-60.]"

Even in medicine, without pre-registered RCTs truth is extremely difficult to come by, with more than one half Kaiser J. More than half of high-impact cancer lab studies could not be replicated in controversial analysis. AAAS Articles DO Group. 2021; of high-impact cancer papers failing to be replicated, and with one half of RCTs without pre-registration of positive outcomes being spun Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382. by researchers as providing benefit when there’s none. And this is in medicine, which is infinitely more consequential and rigorous than psychology.

Also see: Appendix: I have no trust in sleep scientists.

Decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects

In this section, I outline several lines of evidence that bring me to the conclusion that decreasing sleep by 1-2 hours a night in the long-term has no negative health effects. To summarize:

- A sleep researcher who trains sailors to sleep efficiently in order to maximize their race performance believes that 4.5-5.5 hours of sleep is fine.

- 70% of 84 hunter-gatherers studied in 2013 slept less than 7 hours per day, with 46% sleeping less than 6 hours.

- A single-point mutation can decrease the amount of required sleep by 2 hours, with no negative side-effects.

- A brain surgery can decrease the amount of sleep required by 3 hours, with no negative-side effects.

- Sleep is not required for memory consolidation.

- Claudio Stampi is a Newton, Massachusetts based sleep researcher. But he is not your normal sleep researcher whose career is built on observational studies or p-hacked n=20 experiments that always show “significant” results. He is one of the only sleep researchers with skin in the game: the goal of his research is to maximize performance of sailors by tinkering with their sleep cycles, and he believes that 4.5-5.5 hours of sleep is fine, The article uses the phrase “get by” and does not state that there’s no decrease in performance. However, it does state that the decrease in performance at 3 hours of sleep with lots of naps is 12-25%, so increasing sleep by 50-83% from this, seems unlikely to result in any decrease in performance, compared to 8 hours of sleep (“he had them shift to their three-hour routines. After more than a month, the monophasic group showed a 30 percent loss in cognitive performance. The group that divided its sleep between nighttime and short naps showed a 25 percent drop. But the polyphasic group, which slept exclusively in short naps, showed only a 12 percent drop.”). as long as it’s broken down into core sleep and a series of short (usually 20-minute) naps. Here’s Outside:

“Solo sailing is one of the best models of 24/7 activity, and brains and muscles are required,” Stampi said one day at his home, from which he runs the institute. “If you sleep too much, you don’t win. If you don’t sleep enough, you break.” …

“For those sailors who are seriously competing, Stampi is a necessity,” says Brad Van Liew, a 37-year-old Californian who began working with Stampi in 1998 and went on to become America’s most accomplished solo racer and the winner in his class of the 2002-2003 Around Alone, a 28,000-mile global solo race. “You have to sleep efficiently, or it’s like having a bad set of sails or a boat bottom that isn’t prepared properly.” …

both Golding and MacArthur sleep about the same amount while racing, between 4.5 and 5.5 hours on average in every 24—the minimum amount, Stampi believes, on which humans can get by.

-

In 2013, scientists tracked the sleep of 84 hunter-gatherers from 3 different tribes Yetish G, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Wood B, Pontzer H, Manger PR, Wilson C, McGregor R, Siegel JM. Natural sleep and its seasonal variations in three pre-industrial societies. Current Biology. 2015 Nov 2;25(21):2862-8. (each person’s sleep was measured for about a week but measurements for different groups were taken in different parts of the year). The average amount of sleep among these 84 people was 6.5 hours. Judging by CDC’s “7 hours or more” recommendation, Consensus Conference Panel:, Watson, N.F., Badr, M.S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D.L., Buxton, O.M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D.F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M.A. and Kushida, C., 2015. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(8), pp.931-952. 70% out of these 84 undersleep:

- 6 people slept between 4 and 5 hours

- 19 people slept between 5 and 6 hours

- 34 people slept between 6 and 7 hours

- 21 people slept between 7 and 8 hours

- 4 people slept between 8 and 9 hours

One group of hunter-gatherers (10 people from Tsimane tribe studied in November/December of 2013) slept just 5.6 hours on average.

The authors of this study also note that “None of these groups began sleep near sunset, onset occurring, on average, 3.3 hr after sunset” (they are probably getting too much artificial light… or something).

What I’m getting from all of this is: there’s nothing “natural” about sleeping 7-9 hours. If you think that the amount of sleep hunter-gatherers are getting is the amount of sleep humans have evolved to get, then you should not worry at all about getting 4, 5, or 6 hours of sleep a night.

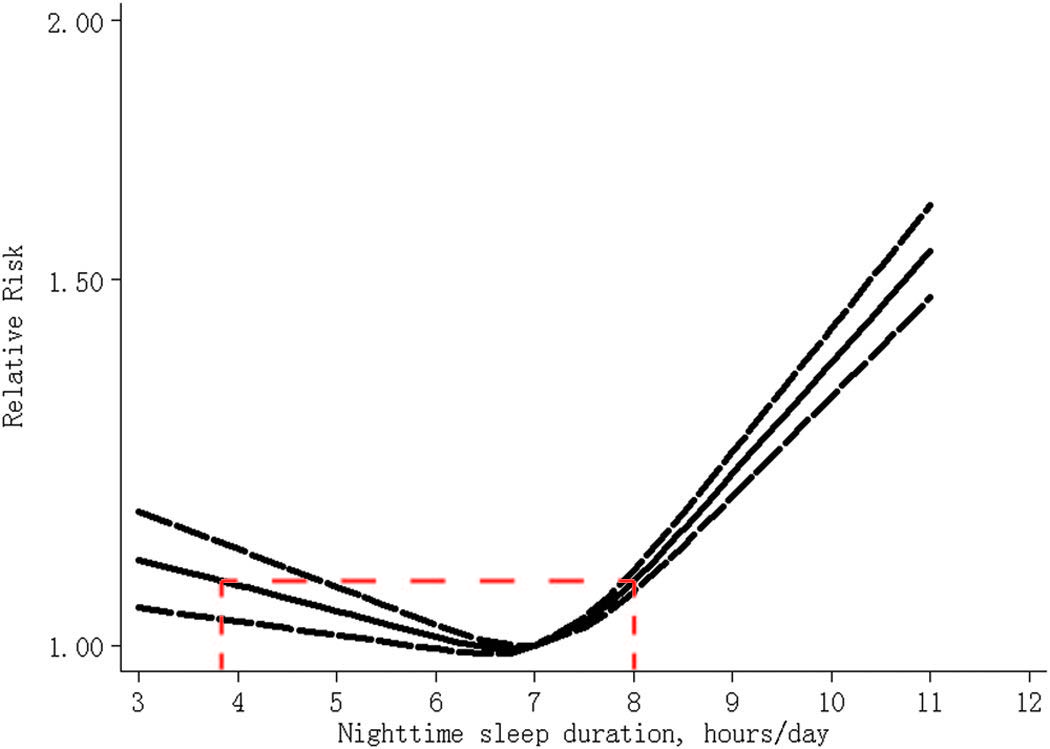

The CDC and the professional sleep researchers pull the numbers out of their asses without any kind of rigorous scientific evidence for their “consensus recommendations”. There’s no causal evidence that sleeping 7-9 hours is healthier than sleeping 6 hours or less. Correlational evidence suggests Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480. that people who sleep 4 hours have the same if not lower mortality as those who sleep 8 hours and that people who sleep 6-7 hours have the lowest mortality.

Figure 4. The dose-response analysis between nighttime sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality. The solid line and the long dash line represent the estimated relative risk and its 95% confidence interval. Note: the red dashed line on the graph is mine. Copied from Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480.Also see: Appendix: Jerome Siegel and Robert Vertes vs the sleep establishment

-

It appears that there is a distinct single-point mutation that allows some people to sleep several hours less than typical on average. A Rare Mutation of β1-Adrenergic Receptor Affects Sleep/Wake Behaviors: Shi G, Xing L, Wu D, Bhattacharyya BJ, Jones CR, McMahon T, Chong SC, Chen JA, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Krystal A. A rare mutation of β1-adrenergic receptor affects sleep/wake behaviors. Neuron. 2019 Sep 25;103(6):1044-55.

We have identified a mutation in the β1-adrenergic receptor gene in humans who require fewer hours of sleep than most. In vitro, this mutation leads to decreased protein stability and dampened signaling in response to agonist treatment. In vivo, the mice carrying the same mutation demonstrated short sleep behavior. We found that this receptor is highly expressed in the dorsal pons and that these ADRB1+ neurons are active during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep and wakefulness. Activating these neurons can lead to wakefulness, and the activity of these neurons is affected by the mutation. These results highlight the important role of β1-adrenergic receptors in sleep/wake regulation.

The study compares carriers of the mutation in one family to non-carriers in the same family and finds that carriers sleep about 2 hours per day less. Given the complexity of sleep and the multitude of its functions, it seems extremely implausible that just one mutation in the β1-adrenergic receptor gene was able to increase its efficiency by about 25%. It seems that it just made carriers sleep less (due to more stimulation of a group of neurons in the brain responsible for sleep/wakefulness) without anything else obviously changing when compared to non-carriers.

-

A similar example of a drop in the amount of sleep required without negative side effects and driven by a single factor was described in Development of a Short Sleeper Phenotype after Third Ventriculostomy in a Patient with Ependymal Cysts. Seystahl K, Könnecke H, Sürücü O, Baumann CR, Poryazova R. Development of a short sleeper phenotype after third ventriculostomy in a patient with ependymal cysts. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014 Feb 15;10(2):211-3. To sum up: a 59-year-old patient had chronic hydrocephalus. An endoscopic third ventriculostomy was performed on him. His sleep dropped from 7-8 hours a night to 4-5 hours a night without him becoming sleepy, he stopped being depressed, and his physical or cognitive performance stayed normal, as measured by the doctors.

-

Sleep is not required for memory consolidation. Jerome Siegel (the author of the hunter-gatherers study mentioned above) writes in Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep: Siegel JM. Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep. Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2021 Mar;7(1):15-8.

Under interference conditions, such as exist during sleep deprivation, subjects, by staying awake, necessarily interacting with the experimenter keeping them awake and experiencing the laboratory environment, will remember more than just the items that are presented. But they may be less able to recall the particular items the experimenter is measuring. This can lead to the mistaken conclusion that sleep is required for memory consolidation [7].

Recent work has, for the first time, dealt with this issue. It was shown that a quiet waking period or a meditative waking state in which the environment is being ignored, produces a gain in recall similar to that seen in sleep, relative to an active waking state or a sleep-deprived state [8–16]. …

REM sleep has been hypothesized to have a key role in memory consolidation [20]. But it has been reported that near total REM sleep deprivation for a period of 14 to 40 days by administration of the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine has no apparent effect on cognitive function in humans [21]. A systematic study using serotonin or norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitors to suppress REM sleep in humans had no deleterious effects on a variety of learning tasks [22, 23]. Humans rarely survive the damage to the pontine region which when discretely lesioned in animals greatly reduces or eliminates REM sleep [20, 23–25]. However, one such subject with pontine damage that severely reduced REM sleep has been thoroughly studied. The studies show normal or above normal cognitive performance and no deficit in memory formation or recall [26•]. It has been claimed that learning results in greater total amounts of sleep, or greater amounts of REM sleep [27], or greater amounts of sleep spindles, or slow wave activity. However, a systematic test of this hypothesis in 929 human subjects with night-long EEG recording found no such correlation with retention [28•].

The entire Scientific Consensus™ about sleep being essential for memory consolidation appears to be heavily flawed, driven by people like Matthew Walker, and making me lose the last remnants of trust in sleep science that I had.

Also see:

- Appendix: how I wake up after 6 or less hours of sleep

- Appendix: anecdotes about long-term sleep deprivation

- Appendix: the idea that sleep’s purpose is metabolite clearance, if not total bs, is massively overhyped

Conclusion

Chadwick worked for several nights straight without sleep on the seminal discovery [of the neutron, for which he was awarded the 1935 Nobel in physics]. When he was done he went to a meeting of the Kapitza Club at Cambridge and gave a talk about it, ending with the words, “Now I wish to be chloroformed and put to sleep”.

I’m not what they call a “natural short sleeper”. If I don’t restrict my sleep, I often sleep more than 8 hours and I still struggle with getting out of bed. I used to be really scared of not sleeping enough and almost never set the alarm for less than 7.5 hours after going to bed.

My sleep statistics tells me that I slept an average of 5:25 hours over the last 7 days, 5:49 hours over the last 30 days, and 5:57 over the last 180 days hours, meaning that I’m awake for 18 hours per day instead of 16.5 hours. I usually sleep 5.5-6 hours during the night and take a nap a few times a week when sleepy during the day.

This means that I’m gaining 33 days of life every year. 1 more year of life every 11 years. 5 more years of life every 55 years.

Why are people not all over this? Why is everyone in love with charlatans who say that sleeping 5 hours a night will double your risk of cancer, make you pre-diabetic, and cause Alzheimer’s, despite studies showing that people who sleep 5 hours have the same, if not lower, mortality than those who sleep 8 hours? Convincing a million 20-year-olds to sleep an unnecessary hour a day is equivalent, in terms of their hours of wakefulness, to killing 62,500 of them.

I wrote large chunks of this essay having slept less than 1.5 hours over a period of 38 hours. I came up with and developed the biggest arguments of it when I slept an average of 5 hours 39 minutes per day over the preceding 14 days. At this point, I’m pretty sure that the entire “not sleeping ’enough’ makes you stupid” is a 100% psyop. It makes you somewhat more sleepy, yes. More stupid, no. I literally did an experiment in which I tried to find changes in my cognitive ability after sleeping 4 hours a day for 12-14 days, I couldn’t find any. My friends who I was talking to a lot during the experiment simply didn’t notice anything.

What do I lose due to sleeping 1.5 hours a day less? I’m somewhat more sleepy every day and staying awake during boring calls is even more difficult now. On the other hand, just a prospect of playing an exciting video game, makes me 100% alert even after sleeping for 2-3 hours. Related: Horne JA, Pettitt AN. High incentive effects on vigilance performance during 72 hours of total sleep deprivation. Acta psychologica. 1985 Feb 1;58(2):123-39. There’s no guarantee that what I’m doing is healthy after all, although, as I explained above, I think that it’s extremely unlikely due to likely adaptation, and likely beneficial effects of sleep deprivation (e.g. increased BDNF, less susceptibility to depression), and since I take a 20-minute nap under my wife’s watch whenever I don’t feel good.

An internationally known expert on acute sleep deprivation Dr. ALIEN SOLDIER (twitter account deleted).

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank (in reverse alphabetic order): Misha Yagudin, Guy Wilson, Bart Sturm, Ulysse Sabbag, Stephen Malina, Gavin Leech, Anastasia Kuptsova, Jake Koenig, Aleksandr Kotyurgin, Alexander Kim, Basil Halperin, Jeremy Hadfield, Steve Gadd, and Willy Chertman for reading drafts of this essay and for disagreeing with many parts of it vehemently. All errors mine.

Citation

Cite as:

Guzey, Alexey. Theses on Sleep. Guzey.com. 2022 February. Available from https://guzey.com/theses-on-sleep/.

Or download a BibTeX file here.

Notes

- One popular sleep tip I’ve come to wholeheartedly believe is the importance of waking up at the same time: from my experience, it does really seem that the organism adjusts the time it is ready to wake up if you keep a consistent schedule.

- I think sleepiness indicates boringness of the environment much more than it indicates the physiological need for sleep. It’s an indicator of build up of sleep-promoting chemicals coupled with the boringness of the environment

- observation: I find staying awake during boring lectures impossible and reliably fall asleep during them, regardless of the amount of sleep I’m getting

- observation: I can play video games with little sleep for several days and feel 100% alert (a superstimulus of its own, but still a valuable observation)

- observation: I become sleepy when I’m working on something boring and difficult

Common objections

Objection: “When I’m underslept I notice that I’m less productive.”

Answer:

-

Yes, this is expected as per the analogy to exercise I make above. After exercise you are tired but over time you become stronger.

-

It might be that undersleeping itself causes you to be less productive. However, it might also be the case that there’s an upstream cause that results in both undersleeping and lack of productivity. I think either could be the case depending on the person but understanding what exactly happens is much harder than people typically appreciate when they notice such co-occurrences.

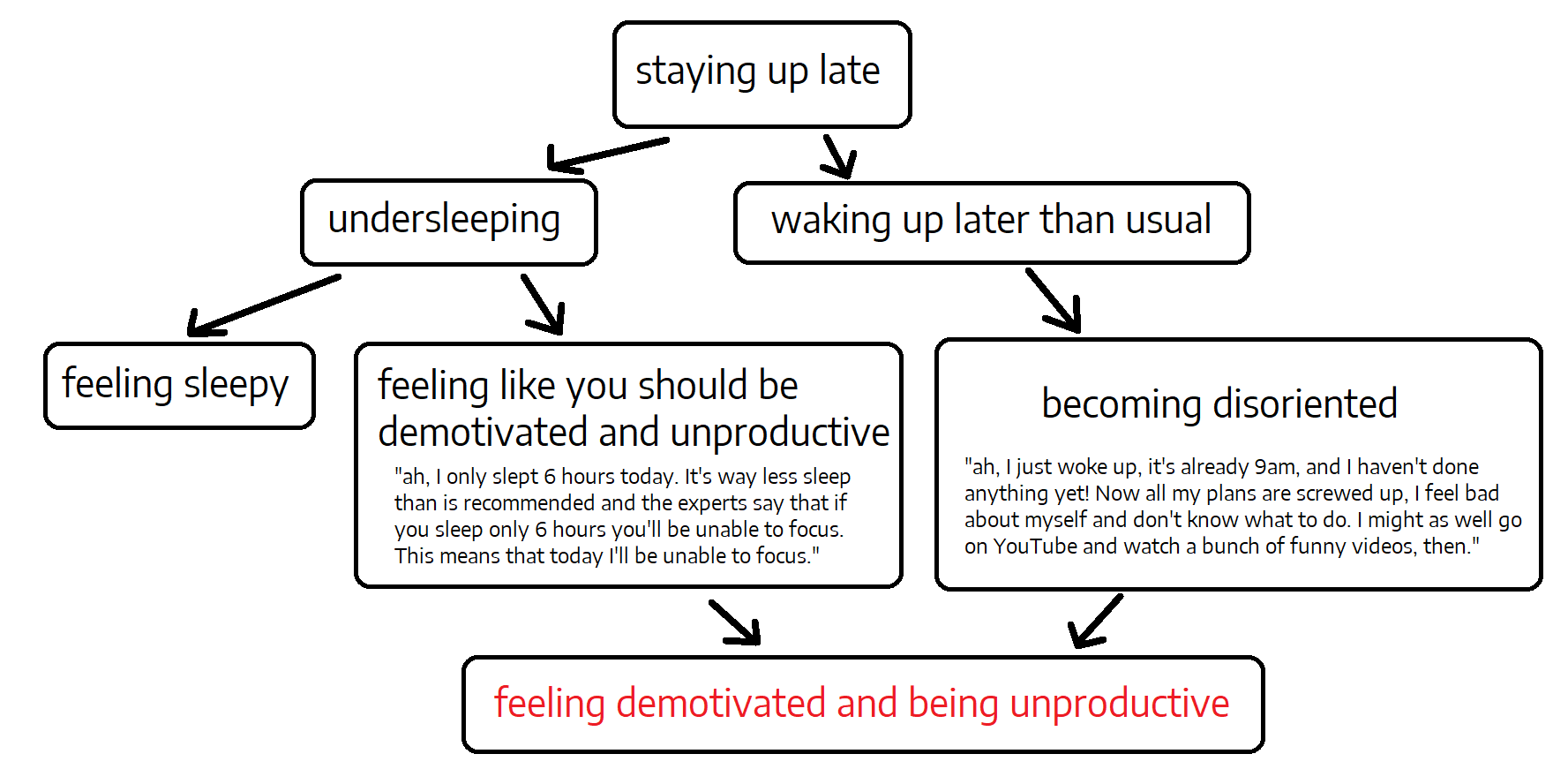

Figure 5. Causal graph of the "staying up late and feeling demotivated and being unproductive scenario."

As Nick Wignall notes on Twitter:

People are also not great at distinguishing true sleepiness from tiredness.

Analogy would be: of all the times when you feel hungry, how much of that is true hunger vs a craving?

Also related: when people say that e.g. they have a small child, are doing medical residency, etc. and feel terrible due to undersleep, note that there’s a big difference between being randomly forced to not sleep when you want to sleep and managing one’s sleep consciously. The analogy would be to saying that fasting is bad because if you are forbidden by someone from eating randomly throughout the day.

Objection: “Driving when you are sleepy is dangerous, therefore you are wrong.”

Answer: Yep, I agree that driving while being sleepy is dangerous and I don’t want anyone to drive, to operate heavy machinery, etc. when they are sleepy. This, however, bears no relationship on any of the arguments I make.

Objection: “The graph that shows more sleep being associated with higher doesn’t tell us anything because sick people tend to sleep more.”

Answer: It is true that some diseases lead to prolonged sleep. However, some diseases also lead to shortened sleep. For example, many stroke patients suffer from insomnia Sterr A, Kuhn M, Nissen C, Ettine D, Funk S, Feige B, Umarova R, Urbach H, Weiller C, Riemann D. Post-stroke insomnia in community-dwelling patients with chronic motor stroke: physiological evidence and implications for stroke care. Scientific Reports. 2018 May 30;8(1):8409. and people with fatal familial insomnia struggle with insomnia. Therefore, if you want to make the argument that the association between longer sleep and higher mortality is not indicative of the effect of sleep, you have to accept that the same is true about shorter sleep and higher mortality.

Appendix: I have no trust in sleep scientists

Why do I bother with all of this theorizing? Why do I think I can discover something about sleep that thousands of them couldn’t discover over many decades?

The reason is that I have approximately 0 trust in the integrity of the field of sleep science.

As you might be aware, 2 years ago I wrote a detailed criticism of the book Why We Sleep written by a Professor of Neuroscience at psychology at UC Berkeley, the world’s leading sleep researcher and the most famous expert on sleep, and the founder and director of the Center for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley, Matthew Walker.

Here are just a few of biggest issues (there were many more) with the book.

-

Walker wrote: “Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer”, despite there being no evidence that cancer in general and sleep are related. There are obviously no RCTs on this, and, in fact, there’s not even a correlation between general cancer risk and sleep duration.

-

Walker falsified a graph from an academic study in the book.

-

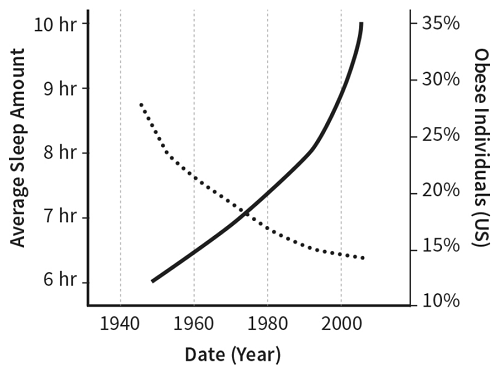

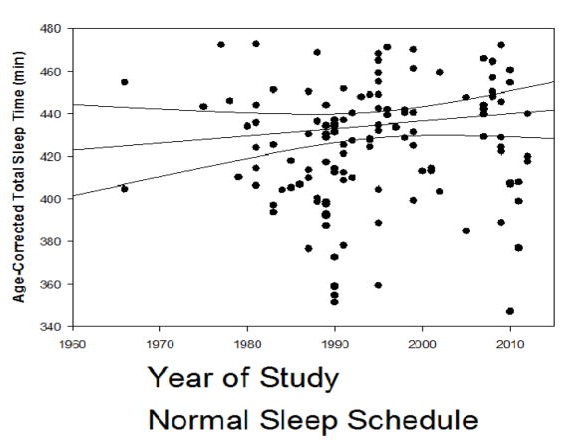

Walker outright fakes data to support his “sleep epidemic” argument. The data on sleep duration Walker presents on the graph below simply does not exist:

Figure 6. Sleep loss and obesity. Country not specified for sleep data. Copied from Walker M. Why we sleep: Unlocking the power of sleep and dreams. Simon and Schuster; 2017 Oct 3.

Here’s some actual data on sleep duration over time:

Figure 7. Association of year of study with age-adjusted total sleep time (min) for studies in which subjects followed their usual sleep schedule. Copied from Youngstedt SD, Goff EE, Reynolds AM, Kripke DF, Irwin MR, Bootzin RR, Khan N, Jean-Louis G. Has adult sleep duration declined over the last 50+ years?. Sleep medicine reviews. 2016 Aug 1;28:69-85.

By the time my review was published, the book had sold hundreds of thousands if not millions of copies and was praised by the New York Times, The Guardian, and many other highly-respected papers. It was named one of NPR’s favorite books of 2017 while Walker went on a full-blown podcast tour.

Did any sleep scientists voice the concerns they with the book or with Walker? No. They were too busy listening to his keynote at the Cognitive Neuroscience Society 2019 meeting.

Did any sleep scientists voice their concerns after I published my essay detailing its errors and fabrications? No (unless you count people replying to me on Twitter as “voicing a concern”).

Did Walker lose his status in the community, his NIH grants, or any of his appointments? No, no, and no.

I don’t believe that a community of scientists that refuses to police fraud and of which Walker is a foremost representative (recall that he is the director of the Center for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley) could be a community of scientists that would produce a trustworthy and dependable body of scientific work.

Appendix: the idea that sleep’s purpose is metabolite clearance, if not total bs, is massively overhyped

Specifically, the original 2013 paper Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O’Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. science. 2013 Oct 18;342(6156):373-7. accumulated more than 3,000 (!) citations in less than 10 years and is highly misleading.

The paper is called “Sleep Drives Metabolite Clearance from the Adult Brain”. The abstract says:

The conservation of sleep across all animal species suggests that sleep serves a vital function. We here report that sleep has a critical function in ensuring metabolic homeostasis. Using real-time assessments of tetramethylammonium diffusion and two-photon imaging in live mice, we show that natural sleep or anesthesia are associated with a 60% increase in the interstitial space, resulting in a striking increase in convective exchange of cerebrospinal fluid with interstitial fluid. In turn, convective fluxes of interstitial fluid increased the rate of β-amyloid clearance during sleep. Thus, the restorative function of sleep may be a consequence of the enhanced removal of potentially neurotoxic waste products that accumulate in the awake central nervous system.

At the same time, the paper found that anesthesia without sleep results in the same clearance (paper: “Aβ clearance did not differ between sleeping and anesthetized mice”), meaning that clearance is not caused by sleep per se, but instead only co-occurrs with it. Authors did not mention this in the abstract and mistitled the paper, thus misleading the readers. As far as I can tell, literally nobody pointed this out previously.

And on top of all of this “125I-Aβ1-40 was injected intracortically”, meaning that they did not actually find any brain waste products that would be cleared out. This is an exogenous compound that was injected god knows where disrupting god knows what in the brain.

Appendix: anecdotes about acute sleep deprivation

Max Levchin in Founders at Work:

The product wasn’t really finished, and about a week before the beaming at Buck’s I realized that we weren’t going to be able to do it, because the code wasn’t done. Obviously it was really simple to mock it up—to sort of go, “Beep! Money is received.” But I was so disgusted with the idea. We have this security company; how could I possibly use a mock-up for something worth $4.5 million? What if it crashes? What if it shows something? I’ll have to go and commit ritual suicide to avoid any sort of embarrassment. So instead of just getting the mock-up done and getting reasonable rest, my two coders and I coded nonstop for 5 days. I think some people slept; I know I didn’t sleep at all. It was just this insane marathon where we were like, “We have to get this thing working.” It actually wound up working perfectly. The beaming was at 10:00 a.m.; we were done at 9:00 a.m.

/u/CPlusPlusDeveloper on Gwern’s Writing in the Morning:

We know that acute sleep deprivation seems to have a manic and euphoric effect on at least some percent of the population some percent of the time. For example staying up all night is one of the most effective ways to temporarily aleve depression. Of course the problem is that chronic sleep deprivation has the opposite effect, and the temporary mania and euphoria is not sustainable.

My speculative take is that whatever this mechanism, it was the main reason you experienced a productivity boost. By waking up early you intentionally were fighting against your chronobiology, hence adding an element of acute sleep deprivation regardless of how many hours you got the night before. That mania fuels an amphetamine like focus.

The upshot, if my hypothesis is true, is that waking up early would not produce similar gains if you did it everyday. Like the depressive who stays up all night, it may feels like you’ve discovered an intervention that will pay lasting gains. But if you were to actually make it part of your recurring lifestyle, the benefits would stop, and eventually the impact would work in reverse.

Along those lines that’s probably why you naturally tend to stop conforming to that pattern after a few days. As acute sleep deprivation becomes chronic, you’re most likely intuitively recognizing that the pattern has crossed over to the point of being counter-productive.

Lots of writers and software engineers note that their creative juices start flowing by evening extending late into the night - I think this phenomenon is closely related to the one described in the comment above.

sleep anecdote- In undergrad I had zero sleep before several major tests; also before quals in grad school. Basically wouldn’t sleep before things I really considered important (this included morning meetings I didn’t want to miss!). On such occasions I would feel:

- miserable, then

- absurd and in a good humor, weirdly elated, then

- Super PumpedTM, and

really sharp when the test (or whatever) actually started.

Appendix: a well-documented case-study of a person living without sleep for 4 months

Total Wake: Natural, Pathological, and Experimental Limits to Sleep Reduction, Panchin Y, Kovalzon VM. Total Wake: Natural, Pathological, and Experimental Limits to Sleep Reduction. Frontiers in neuroscience. 2021 Apr 7;15:288. quoting Le sommeil, la conscience et l’éveil: Jouvet M. Le sommeil, la conscience et l’éveil. Odile Jacob; 2016 Mar 9.

There is such pathology as Morvan’s disease, in which quasi-wakefulness, which lasted 3,000 h (more precisely, 2,880), or 4 months, was not accompanied by sleep rebound, since the sleep generation system itself was disturbed.” Throughout this period the patient was under continuous polysomnographic control, so his agrypnia was confirmed objectively. Jouvet conclude that “… slow wave (NREM) and paradoxical (REM) sleep are not necessary for life (at least for 4–5 months for the first and about 8 months for the second), and we cannot consider their suppression to be the cause of any serious disorders in the body. A person who had lack of sleep and dreams for 4 months, of which there are only a few minutes of nightly hallucinations, can turn out to read newspapers during the day, make plans, play cards and win, and at the same time lie on the bed in the dark all night without sleep! In conclusion, we admit: this observation makes most theories about the functions of sleep and paradoxical (REM) sleep obsolete at once, but offers nothing else

Appendix: anecdotes about long-term sleep deprivation

I once tried to cheat sleep, and for a year I succeeded (strong peak-performance-sailing vibes):

In the summer of 2009, I was finishing the first—and toughest—year of my doctorate. …

To keep up this crazy sleep schedule, I always needed a good reason to wake up the next morning after my 3.5-hour nighttime sleep. So before I went to bed, I reviewed the day gone past and planned what I would do the next day. I’ve carried on with this habit, and it serves me well even today.

But the Everyman schedule was reasonably flexible. Some days when I missed a nap, I simply slept a little more at night. There were also days when I couldn’t manage a single nap, but it didn’t seem to affect me very much the next day.

To the surprise of many, and even myself, I had managed to be on the polyphasic schedule for more than a year. But then came a conference where for a week I could not get a single nap. It was unsettling but I was sure I would be able to get back to sleeping polyphasic without too much trouble.

I was wrong. When I tried to get back into the schedule, I couldn’t find the motivation to do it; I didn’t have the same urgent goals that I had had a year ago. So I returned to sleeping like an average human.

James Gleck in Chaos on Mitch Feigenbaum:

In the spring of 1976 he entered a mode of existence more intense than any he had lived through. He would concentrate as if in a trance, programming furiously, scribbling with his pencil, programming again. He could not call C division for help, because that would mean signing off the computer to use the telephone, and reconnection was chancy. He could not stop for more than five minutes’ thought, because the computer would automatically disconnect his line. Every so often the computer would go down anyway, leaving him shaking with adrenaline. He worked for two months without pause. His functional day was twenty-two hours. He would try to go to sleep in a kind of buzz, and awaken two hours later with his thoughts exactly where he had left them. His diet was strictly coffee. (Even when healthy and at peace, Feigenbaum subsisted exclusively on the reddest possible meat, coffee, and red wine. His friends speculated that he must be getting his vitamins from cigarettes.)

In the end, a doctor called it off. He prescribed a modest regimen of Valium and an enforced vacation. But by then Feigenbaum had created a universal theory.

Ryan Kulp’s experience with decreasing the amount of sleep by several hours:

i began learning to code in 2015. since i was working full-time i needed to maximize after-hours to learn quickly. i experimented for 10 days straight… go to sleep at 4am, wake up at 8am for work. felt fine.

actually, the first 5-10 minutes of “getting up” after 3-4 hours of sleep sucks more than if i sleep ~8 hours. but after 15 mins of moving around, a shower, etc, i feel as if i slept 8 hours.

since then i’ve routinely slept 4-6 hours /day and definitely been more productive. i think if more people experimented for themselves and had the same “aha” moment i did (that you feel fine after the initial gut-wrenching “i slept too little” reaction), they’d get more done too.

This is a very good point that shows that: there’s (1) how sleepy we feel when waking up and (2) how sleepy we feel during the day. (2) is probably more important but most people are focused on (1) and the implicit assumption is that poor (1) leads to (2) – which is unwarranted.

Also: https://twitter.com/BroodVx/status/1492227577896787969,

Appendix: how I wake up after 6 or less hours of sleep

Nabeel Qureshi writes:

you’re combining two things here: (1) your brain is overpowered by the comfy soft temp-controlled bed (2) you’re bored. they might both be right but i think you conflate them, and they’re separate arguments. this is important bc i think the strongest counterargument to what you’re saying is the classic experience of: you force yourself to wake up early (say 6), you have a project you’re genuinely excited about (hence #2 is false), but when you sit down to work, you’re tired and can’t quite focus. in this scenario, i think your theory would say that i’m not really that excited about what i’m doing, because if i were (see video game argument) then i’d be awake. i’d disagree and say that the researcher should just go take a nap, and they’ll probably be able to make more progress per hour than the extra hours they gain… trying to force yourself to do something while underslept, subjectively, feels hellish. i’m sure you’ve had this experience - did you figure out a workaround?

It is completely true that if you are excited by a project but it’s not super stimulating, it’s still very easy to wake up after less than usual number of hours of sleep and feel sleepy and terrible. This is true for me as well. I found a solution to this: instead of heading straight to the computer, I first unload the clean plates from the dishwasher and load it with dirty plates. This activity is quite special in that it is:

- Physical (includes lots of moving around physical objects to/from around the kitchen).

- Why this matters: moving around wakes up the body much better than just sitting.

- Mental (the objects are always in different places, the arrangement of them within the dishwasher is always somewhat different and you need to effectively solve a new spatial organization problem every day to load everything efficiently).

- Why this matters: moving around in automatic pre-defined movements eventually results in the brain just performing these movements on autopilot without waking up.

- Very moderate in effort (no lifting of heavy things, nothing that requires complex concentration).

- Why this matters: I and people I know tend to find intense physical activities right after waking up really unpleasant and somewhat nauseating.

In about 90% of the cases, 10 minutes later when I’m done with the dishwasher, I find that I’m fully awake and don’t actually want to sleep anymore. In the remaining 10% of the cases, I stay awake and work until my wife wakes up and then go take a 20-minute nap under her watch (and take as many 20-minute naps as I need during the day, although I only end up taking a few naps a week and rarely more than one per day, unless I’m sick).

Appendix: Elon Musk on working 120 hours a week and sleep

CNBC:

On Tesla’s first-quarter earnings conference call in May, Musk referred to inquiries from Wall Street analysts as “boring, bonehead questions” and as “so dry. They’re killing me.” On the next earnings conference call in August, Musk said he was sorry for “being impolite” on the previous call.

“Obviously I think there’s really no excuse for bad manners and I was violating my own rule in that regard. There are reasons for it, I got no sleep, 120 hour weeks, but nonetheless, there is still no excuse, so my apologies for not being polite on the prior call,” Musk said.

Later in August, in conversation with the New York Times, Musk reported using prescription sleep medication Ambien to sleep.

“Yeah. It’s not like for fun or something,” Musk told Swisher Wednesday. “If you’re super stressed, you can’t go to sleep. You either have a choice of, like, okay, I’ll have zero sleep and then my brain won’t work tomorrow, or you’re gonna take some kind of sleep medication to fall asleep.”

Musk said he was working such insane hours to get Tesla through the ramp up in production for its Model 3 vehicle. ”[A]s a startup, a car company, it is far more difficult to be successful than if you’re an established, entrenched brand. It is absurd that Tesla is alive. Absurd! Absurd.”

Appendix: Philipp Streicher on homeostasis, its relationship to mania/depression, and on other points I make

First, I wanted to share a way of thinking about some of your findings that builds on the idea of a homeostatic control system (brought to you from engineering via cybernetics). The classic example is a thermostat, which keeps temperature of a room close to a set point. Biology is quite a bit more messy than this, of course, but the body makes use of a plenty of feedback mechanisms to stay close to set points as well. You’re right in pointing out that these set points don’t need to be healthy though. For example, measured via EEG, PTSD patients have alpha power (which primarily modulates neural inhibition in frontal, parietal and occipital areas of the brain) set points far below that of healthy control groups. One way to deal with these suboptimal set points is to simply disrupt the system. Here’s a model that makes this point nicely: imagine all possible brain state dynamics as a two-dimensional plane and place a ball on it which represents the current brain state space. As the ball moves, the brain dynamics change as well (in frequency, phase, amplitude - you name it). On the plane, you have basins that give stability to the brain state, and repellers in the form of hills, as well as random noise and outside interference which drives the ball into various directions. Sometimes the ball will get stuck in basins which are highly suboptimal, but they are deep enough that exploration of other set points is not possible. If the system is disrupted, the ball might get jolted out of its basin though, and be again able to fall into a more optimal position.

With that said, there’s plenty of evidence that stability in itself (even within better basins) is suboptimal for perfect health, because contexts change. For example, people who are very physically healthy (athletes, for example), tend to have far greater variance in the time interval between individual heart beats (heart rate variability) than even the average person, and as the average person gets healthier, their heart rate variability increases as well. Basically, the body becomes more resilient by introducing a noise signal that produces chaotic fluctuations to homeostatic control mechanisms (controlled allostasis) and there are good reasons to think that this is true of psychological health as well.

Because of this, I think that you’re right in suggesting that varying the amount of time you sleep is a good thing - especially if you’re currently struggling with depression or mania. Not even necessarily because sleep per se is the culprit, but because it might dislodge a ball stuck in a suboptimal basin, so to speak. Depressed people tend to oversleep, people with mania tend to sleep too little, so steering in the opposite direction is only logical. For perfectly healthy people, sleep cycling is probably the best way to go - kind of a mirroring the logic of heart rate variability: introduce some noise to keep your body on your toes. It’s just like fasting, working out, cold exposure, saunas, etc. - it’s al about producing stressors on the body which stir up repair processes which keep you healthy (and biologically younger). I have done plenty of self-experiments with polyphasic 5-6 hour sleeping (similar to the the approach studied by Stampi, who you mentioned), with no negative consequences. The main thing that makes it impractical is that intermittent napping is sometimes hard to combine with professional responsibilities and a social life.

As a side note, because you ask the question about why depressed people sleep longer, and people with mania sleep less, the answer to this is very likely highly multi-causal. With that said, I wanted to point out that depressed people generally exhibit excessive alpha activity in eyes-open waking states, which normally becomes more pronounced in people as they drift off to sleep (because of the neural inhibition function). We also have reason to believe that it mediates between BDNF and subclinical depressed mood, so that’s a link to something else you talk about in your article. As for mania, I haven’t looked at this myself, but I remember hearing that it’s almost a mirror image, with generally decreased synchronisation of slower oscillations and heightened faster rhythms, generally associated with greater arousal and wakefulness.

One last thing: as you point out, sleep is likely not required for memory retention. Any claim that sleep is about any specific cognitive function should be suspect on the principle that the phenomenon of sleep predates the development of organisms with brains - it can’t have evolved specifically for something as high-level as memory retention. It’s more likely about something more basic like general metabolic health.

Appendix: Jerome Siegel and Robert Vertes vs the sleep establishment

Time for the Sleep Community to Take a Critical Look at the Purported Role of Sleep in Memory Processing Vertes RP, Siegel JM. Time for the sleep community to take a critical look at the purported role of sleep in memory processing. Sleep. 2005 Oct 1;28(10):1228-9. by Robert Vertes and Jerome Siegel (a reply to Walker claiming that the debate on memory processing in sleep is essentially settled):

The present ‘debate’ was sparked by an editorial by Robert Stickgold in SLEEP on an article in that issue by Schabus et a on paired associate learning and sleep spindles in humans

Regarding Stickgold’s editorial, I was particularly troubled by his opening statement, as follows: “The study of sleep-dependent memory consolidation has moved beyond the question of whether it exists to questions of its extent and of the mechanisms supporting it”. He then proceeded to cite evidence justifying this statement. Surprisingly, there was no mention of opposing views or a discussion of data inconsistent with the sleep-memory consolidation (S-MC) hypothesis. It seemed that the controversial nature of this issue should have at least been acknowledged, but apparently to do so would have undermined Stickgold’s position that the door is closed on this debate and only the fine points need be resolved. …

- By all accounts, sleep does not serve a role in declarative memory. As reviewed by Smith, with few exceptions, reports have shown that depriving subjects of REM sleep does not disrupt learning/memory, or exposure to intense learning situations does not produce subsequent increases in REM sleep. Smith concluded: “REM sleep is not involved with consolidation of declarative material.” The study by Schabus et al (see above) is another example that the learning of declarative material is unaffected by sleep. They reported that subjects showed no significant difference in the percentage of word-pairs correctly recalled before and after 8 hours of sleep. Or as Stickgold stated in his editorial [the editorial Vertes and Siegel are replying to], “Performance in the morning was essentially unchanged from the night before”. It would seem important for Stickgold/Walker to acknowledge that the debate on sleep and memory has been reduced to a consideration of procedural memory – to the exclusion of declarative memory. If there are exceptions, they should note.

- Several lines of evidence indicate that REM sleep is not involved in memory processing/consolidation – or at least not in humans. Perhaps the strongest argument for this is the demonstration that the marked suppression or elimination of REM sleep in individuals with brainstem lesions or on antidepressant drugs has no detrimental effect on cognition. A classic case is that of an Israeli man who at the age of 19 suffered damage to the brainstem from shrapnel from a gunshot wound, and when examined at the age of 33 he showed no REM sleep. The man, now 55, is a lawyer, a painter and interestingly the editor of a puzzle column for an Israeli magazine. Recently commenting on his ‘famous’ patient, Peretz Lavie stated that “he is probably the most normal person I know and one of the most successful ones”. There are several other well documented cases of individuals with greatly reduced or absent REM sleep that exhibit no apparent cognitive deficits. It would seem that these individuals would be a valuable resource for examining the role of sleep in memory. …

In Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep cited above, Siegel notes: Siegel JM. Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep. Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2021 Mar;7(1):15-8.

To critically evaluate this hypothesis [that sleep has a critical role in memory consolidation], we must take “interference” effects into account. If you learn something before or after the experimenter induced learning that is being measured in the typical sleep-memory study, it degrades recall of the tested information. For example if you tell a subject that the capital of Australia is Canberra and then allow the subject to have a normal night’s sleep, there is a high probability that the subject will remember this upon awakening. If on the other hand you tell the subject that the capital of Australia is Canberra, the capital of Brazil is Brasilia, the capital of Canada is Ottawa, the capital of Iceland is Reykjavik, the capital of Libya is Tripoli, the capital of Pakistan is Islamabad, etc., it is much less likely the subject will remember the capital of Australia. The effect of proactive and retroactive interference is dependent on the temporal juxtaposition, complexity, and similarity of the encountered material to the associations being tested. Interference is a well-established concept in the learning literature [1–6]. Under interference conditions, such as exist during sleep deprivation, subjects, by staying awake, necessarily interacting with the experimenter keeping them awake and experiencing the laboratory environment, will remember more than just the items that are presented. But they may be less able to recall the particular items the experimenter is measuring. This can lead to the mistaken conclusion that sleep is required for memory consolidation [7].

Fur Seals Suppress REM Sleep for Very Long Periods without Subsequent Rebound: Lyamin OI, Kosenko PO, Korneva SM, Vyssotski AL, Mukhametov LM, Siegel JM. Fur seals suppress REM sleep for very long periods without subsequent rebound. Current Biology. 2018 Jun 18;28(12):2000-5.

Virtually all land mammals and birds have two sleep states: slow-wave sleep (SWS) and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep [1, 2]. After deprivation of REM sleep by repeated awakenings, mammals increase REM sleep time [3], supporting the idea that REM sleep is homeostatically regulated. *Some evidence suggests that periods of REM sleep deprivation for a week or more cause physiological dysfunction and eventual death [4, 5]. However, separating the effects of REM sleep loss from the stress of repeated awakening is difficult [2, 6]. The northern fur seal (Callorhinus ursinus) is a semiaquatic mammal [7]. It can sleep on land and in seawater. The fur seal is unique in showing both the bilateral SWS seen in most mammals and the asymmetric sleep previously reported in cetaceans [8]. Here we show that when the fur seal stays in seawater, where it spends most of its life [7], it goes without or greatly reduces REM sleep for days or weeks. After this nearly complete elimination of REM, it displays minimal or no REM rebound upon returning to baseline conditions. Our data are consistent with the hypothesis that REM sleep may serve to reverse the reduced brain temperature and metabolism effects of bilateral nonREM sleep, a state that is greatly reduced when the fur seal is in the seawater, rather than REM sleep being directly homeostatically regulated. This can explain the absence of REM sleep in the dolphin and other cetaceans and its increasing proportion as the end of the sleep period approaches in humans and other mammals.

Appendix: more papers I found interesting

The end of sleep: ‘Sleep debt’ versus biological adaptation of human sleep to waking needs: Horne J. The end of sleep:‘sleep debt’versus biological adaptation of human sleep to waking needs. Biological psychology. 2011 Apr 1;87(1):1-4.

It is argued that the latter part of usual human sleep is phenotypically adaptable (without ‘sleep debt’) to habitual shortening or lengthening, according to environmental influences of light, safety, food availability and socio-economic factors, but without increasing daytime sleepiness. Pluripotent brain mechanisms linking sleep, hunger, foraging, locomotion and alertness, facilitate this time management, with REM acting as a ‘buffer’ between wakefulness and nonREM (‘true’) sleep. The adaptive sleep range is approximately 6–9 h, although, a timely short (<20 min) nap can equate to 1 h ‘extra’ nighttime sleep. Appraisal of recent epidemiological findings linking habitual sleep duration to mortality and morbidity points to nominal causal effects of sleep within this range. Statistical significance, here, may not equate to real clinical significance. Sleep durations outside 6–9 h are usually surrogates of common underlying causes, with sleep associations taking years to develop. Manipulation of sleep, alone, is unlikely to overcome these health effects, and there are effective, rapid, non-sleep, behavioural countermeasures. Sleep can be taken for pleasure, with minimal sleepiness; such ‘sleepability’ is ‘unmasked’ by sleep-conducive situations. Sleep is not the only anodyne to sleepiness, but so is wakefulness, inasmuch that some sleepiness disappears when wakefulness becomes more challenging and eventful. A more ecological approach to sleep and sleepiness is advocated.

Long-term moderate elevation of corticosterone facilitates avian food-caching behaviour and enhances spatial memory Pravosudov VV. Long-term moderate elevation of corticosterone facilitates avian food-caching behaviour and enhances spatial memory. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003 Dec 22;270(1533):2599-604.

It is widely assumed that chronic stress and corresponding chronic elevations of glucocorticoid levels have deleterious effects on animals’ brain functions such as learning and memory. Some animals, however, appear to maintain moderately elevated levels of glucocorticoids over long periods of time under natural energetically demanding conditions, and it is not clear whether such chronic but moderate elevations may be adaptive. I implanted wild–caught food–caching mountain chickadees (Poecile gambeli), which rely at least in part on spatial memory to find their caches, with 90–day continuous time–release corticosterone pellets designed to approximately double the baseline corticosterone levels. Corticosterone–implanted birds cached and consumed significantly more food and showed more efficient cache recovery and superior spatial memory performance compared with placebo–implanted birds. Thus, contrary to prevailing assumptions, long–term moderate elevations of corticosterone appear to enhance spatial memory in food–caching mountain chickadees. These results suggest that moderate chronic elevation of corticosterone may serve as an adaptation to unpredictable environments by facilitating feeding and food–caching behaviour and by improving cache–retrieval efficiency in food–caching birds.

Racemic Ketamine as an Alternative to Electroconvulsive Therapy for Unipolar Depression: A Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial (KetECT) (via Tomas Roos): Ekstrand J, Fattah C, Persson M, Cheng T, Nordanskog P, Åkeson J, Tingström A, Lindström M, Nordenskjöld A, Movahed RP. Racemic Ketamine as an Alternative to Electroconvulsive Therapy for Unipolar Depression:: A Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial (KetECT). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021.

Background Ketamine has emerged as a fast-acting and powerful antidepressant, but no head to head trial has been performed, Here, ketamine is compared with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), the most effective therapy for depression.

Methods Hospitalized patients with unipolar depression were randomized (1:1) to thrice-weekly racemic ketamine (0.5 mg/kg) infusions or ECT in a parallel, open-label, non-inferiority study. The primary outcome was remission (Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score ≤10). Secondary outcomes included adverse events (AEs), time to remission, and relapse. Treatment sessions (maximum of 12) were administered until remission or maximal effect was achieved. Remitters were followed for 12 months after the final treatment session.

Results In total 186 inpatients were included and received treatment. Among patients receiving ECT, 63% remitted compared with 46% receiving ketamine infusions (P = .026; difference 95% CI 2%, 30%). Both ketamine and ECT required a median of 6 treatment sessions to induce remission. Distinct AEs were associated with each treatment. Serious and long-lasting AEs, including cases of persisting amnesia, were more common with ECT, while treatment-emergent AEs led to more dropouts in the ketamine group. Among remitters, 70% and 63%, with 57 and 61 median days in remission, relapsed within 12 months in the ketamine and ECT groups, respectively (P = .52).

Conclusion Remission and cumulative symptom reduction following multiple racemic ketamine infusions in severely ill patients (age 18–85 years) in an authentic clinical setting suggest that ketamine, despite being inferior to ECT, can be a safe and valuable tool in treating unipolar depression.

References

Beersma DG, Van den Hoofdakker RH. Can non-REM sleep be depressogenic?. Journal of affective disorders. 1992 Feb 1;24(2):101-8.

Bessone P, Rao G, Schilbach F, Schofield H, Toma M. The economic consequences of increasing sleep among the urban poor. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2021 Aug;136(3):1887-941.

Consensus Conference Panel:, Watson, N.F., Badr, M.S., Belenky, G., Bliwise, D.L., Buxton, O.M., Buysse, D., Dinges, D.F., Gangwisch, J., Grandner, M.A. and Kushida, C., 2015. Joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, 11(8), pp.931-952.

Eckert A, Karen S, Beck J, Brand S, Hemmeter U, Hatzinger M, Holsboer-Trachsler E. The link between sleep, stress and BDNF. European Psychiatry. 2017 Apr;41(S1):S282-.

Ekstrand J, Fattah C, Persson M, Cheng T, Nordanskog P, Åkeson J, Tingström A, Lindström M, Nordenskjöld A, Movahed RP. Racemic Ketamine as an Alternative to Electroconvulsive Therapy for Unipolar Depression:: A Randomized, Open-Label, Non-Inferiority Trial (KetECT). International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021.

Giese M, Unternährer E, Hüttig H, Beck J, Brand S, Calabrese P, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Eckert A. BDNF: an indicator of insomnia?. Molecular psychiatry. 2014 Feb;19(2):151-2.

Goldschmied JR, Rao H, Dinges D, Goel N, Detre JA, Basner M, Sheline YI, Thase ME, Gehrman PR. 0886 Recovery Sleep Significantly Decreases BDNF In Major Depression Following Therapeutic Sleep Deprivation. Sleep. 2019 Apr;42(Supplement_1):A356-.

Horne J. The end of sleep:‘sleep debt’versus biological adaptation of human sleep to waking needs. Biological psychology. 2011 Apr 1;87(1):1-4.

Horne JA, Pettitt AN. High incentive effects on vigilance performance during 72 hours of total sleep deprivation. Acta psychologica. 1985 Feb 1;58(2):123-39.

Kaiser J. More than half of high-impact cancer lab studies could not be replicated in controversial analysis. AAAS Articles DO Group. 2021;

Kaplan RM, Irvin VL. Likelihood of null effects of large NHLBI clinical trials has increased over time. PloS one. 2015 Aug 5;10(8):e0132382.

Lyamin OI, Kosenko PO, Korneva SM, Vyssotski AL, Mukhametov LM, Siegel JM. Fur seals suppress REM sleep for very long periods without subsequent rebound. Current Biology. 2018 Jun 18;28(12):2000-5.

Pravosudov VV. Long-term moderate elevation of corticosterone facilitates avian food-caching behaviour and enhances spatial memory. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 2003 Dec 22;270(1533):2599-604.

Turner EH, Matthews AM, Linardatos E, Tell RA, Rosenthal R. Selective publication of antidepressant trials and its influence on apparent efficacy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008 Jan 17;358(3):252-60.

Rahmani M, Rahmani F, Rezaei N. The brain-derived neurotrophic factor: missing link between sleep deprivation, insomnia, and depression. Neurochemical research. 2020 Feb;45(2):221-31.

Riemann, D., König, A., Hohagen, F., Kiemen, A., Voderholzer, U., Backhaus, J., Bunz, J., Wesiack, B., Hermle, L. and Berger, M., 1999. How to preserve the antidepressive effect of sleep deprivation: A comparison of sleep phase advance and sleep phase delay. European archives of psychiatry and clinical neuroscience, 249(5), pp.231-237.

Seystahl K, Könnecke H, Sürücü O, Baumann CR, Poryazova R. Development of a short sleeper phenotype after third ventriculostomy in a patient with ependymal cysts. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2014 Feb 15;10(2):211-3.

Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480.

Shi G, Xing L, Wu D, Bhattacharyya BJ, Jones CR, McMahon T, Chong SC, Chen JA, Coppola G, Geschwind D, Krystal A. A rare mutation of β1-adrenergic receptor affects sleep/wake behaviors. Neuron. 2019 Sep 25;103(6):1044-55.

Siegel JM. Memory Consolidation Is Similar in Waking and Sleep. Current Sleep Medicine Reports. 2021 Mar;7(1):15-8.

Sterr A, Kuhn M, Nissen C, Ettine D, Funk S, Feige B, Umarova R, Urbach H, Weiller C, Riemann D. Post-stroke insomnia in community-dwelling patients with chronic motor stroke: physiological evidence and implications for stroke care. Scientific Reports. 2018 May 30;8(1):8409.

Vertes RP, Siegel JM. Time for the sleep community to take a critical look at the purported role of sleep in memory processing. Sleep. 2005 Oct 1;28(10):1228-9.

Xie L, Kang H, Xu Q, Chen MJ, Liao Y, Thiyagarajan M, O’Donnell J, Christensen DJ, Nicholson C, Iliff JJ, Takano T. Sleep drives metabolite clearance from the adult brain. science. 2013 Oct 18;342(6156):373-7.

Yetish G, Kaplan H, Gurven M, Wood B, Pontzer H, Manger PR, Wilson C, McGregor R, Siegel JM. Natural sleep and its seasonal variations in three pre-industrial societies. Current Biology. 2015 Nov 2;25(21):2862-8.

Youngstedt SD, Goff EE, Reynolds AM, Kripke DF, Irwin MR, Bootzin RR, Khan N, Jean-Louis G. Has adult sleep duration declined over the last 50+ years?. Sleep medicine reviews. 2016 Aug 1;28:69-85.