Every productivity thought I've ever had, as concisely as possible

created: ; modified:I combed through several years of my private notes and through everything I published on productivity before and tried to summarize all of it in this post.

If you’re unproductive right now

Here’s what you should do if you’ve been procrastinating for an entire day:

- Accept that you won’t do anything today and try not to get angry at yourself

- Set the alarm for the time you will be preparing to go to bed today

- No, really. Do it. It will take 20 seconds

- Procrastinate for the rest of the day

- When the alarm rings, put your laptop and everything you need for work in your backpack

- When you wake up, try to not check social media, email or anything else. Do not take anything out of your backpack

- Get dressed, take your stuff, and go to a library, cafe, whatever else where you either

- never been to

- have been to but never procrastinated within the last 6 months

- While getting to that place, figure out what you want to be doing today

- Do it

- Return home in the evening. Don’t take anything (especially your laptop) out of your backpack. Repeat steps 6-10

Every productivity system stops working eventually and there’s nothing you can do about it

You’ve most likely tried the pomodoro technique. You set the timer for 25 minutes, then take a 5 minute break, then set the timer for 25 minutes again, then at some point you take a longer break and so on. I predict that pomodoro technique eventually broke down for the following reasons:

- you stopped adhering strictly to 5 minute breaks and they started turning into 6-7-10-15-20-or-more minute breaks

- you’ve gained an aversion towards 25 minute timers, even while remembering that you should set them, and started finding excuses like “oh this task is too short”, “oh i don’t need a pomo right now”, “i will wait till round time (:00 or :30) and start the pomo then” and these excuses started happening more and more frequently

- you started to outright forget about pomodoros, instead just doing your stuff the old way and once in a while realizing that you should’ve been running a pomodoro

It seems that every productivity trick / system stops working in exactly the same way I described above. Most productivity tricks develop aversion around them. All of them lose salience.

The only way to avoid encountering problems with productivity is to make the stuff you want to be doing in the long-term to be the most exciting stuff you can do at any moment in time, which is perhaps possible if you, e.g. work at a startup, but is untenable in almost every situation.

Context intentionality as the key difference between home and every other place on planet earth

You never wake up at work having forgotten to fill out to dos for the day and feeling slightly depressed.

However awesome you feel you are, this does occasionally happen at home.

Home is the default place. Home lacks intentionality, which means that sometimes you will feel that “I need to do something” rather than “I will do something something specific right now”. As Kaj Sotala puts it: “I’m starting to suspect that I may have MASSIVELY underestimated the negative motivational impact of not having a clear sense of one’s next action in a project. …” (a).

Having no clear idea what to do next increases the probability that you won’t feel like following all the rules you came up with massively. The only solution I know is to avoid working from home as much as you can.

If you aren’t working from home, your workplace should be at least a couple of minutes away (better: an hour away), so that you would not fall into the same trap with it and always had the time to think on what specifically you’re going to do once there. This is also why designating a special room at home as an “office” is probably a bad idea: you will frequently enter it on autopilot, without intentionality.

Thus, even if you can work at home, you probably shouldn’t. I personally try leave home as early as possible, go to the university, and return home as late as possible.

A trick to aid leaving home and going to work someplace else is to try explicitly forbidding doing anything productive at home. This way, you can no longer tell yourself you’ll start working “soon” and then proceed to waste the entire day procrastinating.

Interlude: “eliminate the distractions” is the worst productivity advice I’ve ever seen

With my present system, YouTube, reddit, agar.io, etc. are always just two clicks away, but it doesn’t seem to matter at all. And yet, when I had StayFocusd installed with Nuclear Option turned on (forbidding to visit any sites that aren’t on the white list), I picked up Windows Minesweeper and Solitaire, would often literally bang on the keyboard staring at the monitor wanting to scream and eventually found out a way to uninstall StayFocusd even when I purposely made it — as I thought — impossible to do so.

The very fact that your to do list feels ughy means you’re doing something wrong. The very fact that you need to fight the urges to procrastinate means you’re doing it wrong. The utility function itself is warped in fucked up contexts.

How I work and rest, how my system is different from all the others, and why I like it so much

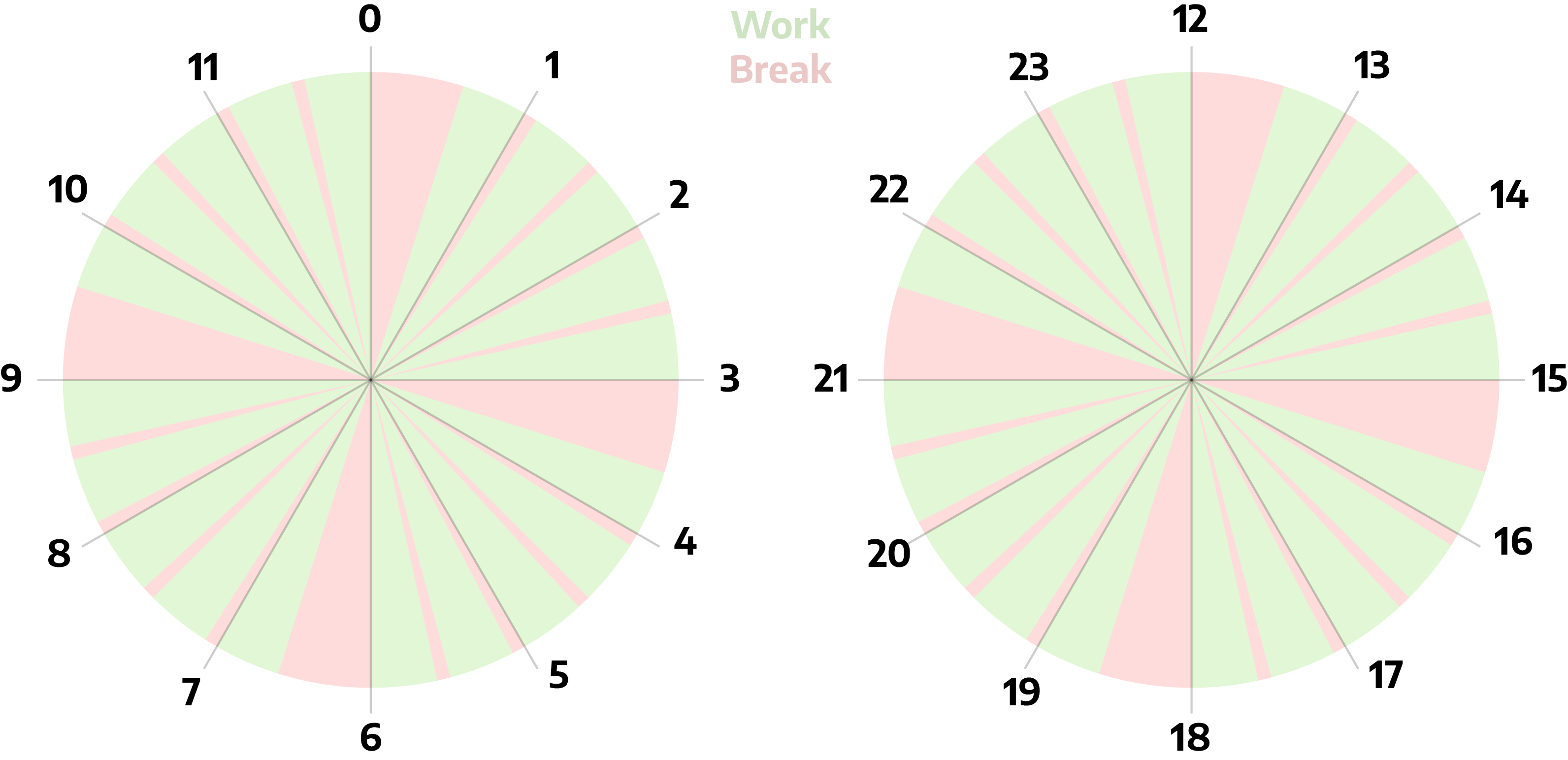

For the last several years, all Did I hear somebody say “preference for routine”? my working time has been structured as follows:

- work for 25 minutes from :05 to :30

- take a 5 minute break from :30 to :35

- work for 25 minutes from :35 to :00

- take a 5 minute break from :00 to :05

- every three hours (at 12-3-6-9) the :05-:30 work cycle is substituted for a break, which lasts 35 minutes.

For example

- work: 9:35-10:00

- break: 10:00-10:05

- work: 10:05-10:30

- break: 10:30-10:35

- work: 10:35-11:00

- break: 11:00-11:05

- work: 11:05-11:30

- break: 11:30-11:35

- work: 11:35-12:00

- break: 12:00-12:35

It’s important for me my clock shows seconds, therefore I could know the start/end of pomos/breaks precisely, instead of constantly trying to guess them. On Windows I use T-Clock.

But didn’t I just write that every productivity system breaks down eventually? Yep, this one breaks down as well. However, I found that this arrangement:

- prolongs the period during which the system works.

- provides me with 625 minutes of work, interspersed with 275 minutes of breaks (provided my workday is 15 hours). This ratio of work / breaks means that I

- have a relatively easy time convincing myself to put off impulsive things (because the maximum waiting time is less than 2.5 hours — until the next long break)

- don’t burn out, since such a large portion of my day is specifically dedicated to doing pleasurable, rewarding in the short-term stuff

- is impossible to forget. Frequently, we simply forget about productivity tricks. Once whole life is built around one, it becomes pretty difficult to forget about it.

You may say, “but isn’t this basically Pomodoro Technique TM?” Kind of. There are several important differences.

- I don’t care about doing only full pomodoros: suppose, I got home at 20:15. Do I dick around and wait till 20:35 to start a pomo? No. 20:15 is time during which I’m working, so I get to work, and then round this pomo up or down , depending on the circumstances.

- I don’t care about pomos being “distraction-free”: suppose, I got distracted in the middle of a pomo. Do I start over? No, I just get back to work, and round this pomo up or down, depending on the circumstances.

The fact that I never have to think “do I work right now or do I take a break right now?” removes most of the friction of the pomodoro technique and means I no longer have to actively think about starting pomodoros. Complice’s LessWrong Study Hall served as an inspiration for me. Given these modifications, it seems that I was able to make my system somewhat of a natural equilibrium.

Some additional rules / heuristics that I follow:

- if I’m in the flow and don’t notice that it’s a break right now, then I skip it. This happens regularly to short breaks; occasionally, e.g. if I’m writing a really exciting post, to long breaks

- I usually divide the stuff I work on in 3 hour chunks. For example, my today’s to do list is:

- -9 work on the most exciting thing about site

- 9-12 productivity post

- 12-13:30 retrospective on college post

- 13:30-15 clean up OneNote

- 15-18 data post

- 18-21 clean up incoming information

- 21- figure out site’s todos

- if I’m obsessed with something, e.g. very exciting research, I usually fill the entire day with it

- if I finish my task in the middle of a pomo, then I move on to the next task immediately

- if I decide that I don’t want to finish the pomo on the task I planned, e.g. after realizing that the textbook I picked is bad, I try to finish the pomo doing as similar to the original task as possible, e.g. starting to read another textbook on the topic

- if I have a thought pop up in my head during a pomo, I write it down to an “Incoming.md” file always open in Notepad. I clean this file up during the breaks and on Sunday

- during the short breaks I’m only allowed non-distractive stuff, i.e. social media, email, most of reddit, slack are prohibited but

- if I have an ongoing conversation with someone, then during the next short break I’m allowed to check if the person wrote anything and reply to them

- if I think the conversation does not wait, then set the phone timer for 5 minutes, and open the conversation then

- if I need to open a specific email conversation, I go to https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#search/NAMELASTNAMEORTOPIC, which, along with hidden number of unread messages, means I don’t get distracted

- if I need to open my email inbox, I think if I can wait till the long break

- if I can’t, set the phone timer for 5 minutes, and open email then

- if I can, open the “Incoming.md” file and write the thing I want to check there, so I don’t forget about it

- if I need to open Twitter / FB for some reason

- open it incognito, so that I don’t see my timeline, notifications, and DMs

- if I need to use my account, e.g. to tweet something or to write someone

- write the tweet down and wait till the long break

- set the phone timer for 5 minutes, and open Twitter then

- if I have an ongoing conversation with someone, then during the next short break I’m allowed to check if the person wrote anything and reply to them

- Chrome

- if I need to open a webpage for something, I’m only allowed to get one page away from what is immediately needed for the task, e.g. I’m writing this post and I want to see what Wikipedia writes about GTD, so I’m allowed to go to GTD, then from GTD to David Allen (and to any other page linked at GTD) but I’m not allowed to open any pages from David Allen. This is the exploration / exploitation tradeoff I enjoy

- if I’m researching something, I’m only allowed to open one page at a time, e.g. when I’m doing a literature review, I open the page, read it, close it, and then open the next one. This prevents me from accumulating a unread tabs too fast

- if I have an ongoing real-time conversation with someone during the long break, I can continue it

- if I’m chatting with someone IRL and I need to open social media because of this, e.g. to send the person I’m chatting with a tweet, I’m allowed to open social media anytime, but only for that specific thing

- if I want to listen to a music, 5 minute timer (because music is somewhat distracting and starting listening to it impulsively is dangerous)

- If I just published a post, I can check social media whenever for the next 6 hours.

I have similar rules for all the other stuff, key being that I must either ensure that I don’t get distracted (incognito) or to make sure I’m not doing anything impulsive (5 minute timer, other person as a trigger). If I don’t follow this, it may be impossible to distinguish between opening, e.g. Twitter because I really needed it or because I really wanted to check my notifications. And if I can’t distinguish between these two, then the simplest explanation is the impulsive one, which means that I’m losing control. Which is really, really bad.

My model of the brain is the following: if it believes that you will do as you planned to do, it will occasionally probe you with impulses, but nothing major, and you will be able to do what your “system 2” Where system 1 is “fast” and system 2 is “slow”. wants to do. But if you start to give in to these impulses, the brain increases their power and their frequency, and naturally, you start to give in more and more, right until the point when you do nothing but what your impulsive brain wants you to do in the moment.

Note that being aware of doing something on impulse doesn’t magically remove the adverse consequences of the action on rules you’re breaking, i.e. being aware of breaking a rule does not make it ok to break it.

2024 update: at some point last year I stopped doing long breaks because together with breaks every 30 minutes they mean I’m doing “real work” only for 2/3rds of the time, which felt like not being productive enough. This was dumb. These breaks ensure that whenever I have an impulse to go read twitter I can tell myself “just wait 20 minutes until checking notifications” and “just wait 2 hours until going to the home page” and this is magical. Without this ability I end up just going to Twitter and doing random stuff all the time.

This doesn’t mean that I have to check Twitter every 30 minutes. But when things are a bit slow, e.g. I’m thinking hard about something and it’s not going very well and I’m tempted to escape into something immediately rewarding, knowledge that if I really want Twitter, it’s never more than 25 minutes away is a life savior for the ability to concentrate. And if I do concentrate, often I realize that checking Twitter during the break would distract me too much, so I end up not doing it anyway!

Rules are about exceptions

Why the hell does my “some additional rules” list look like the table of contents for War and Peace? Why don’t I just say “distractive stuff allowed only during long breaks”? Because rules are about exceptions. Exceptions are inevitable. Sometimes I will have to open a social network or check email during pomos. If I didn’t have exceptions explicitly written down, then I would break my rules, thereby decreasing their future strength. I wrote up a formal model of this process in my Bachelor’s thesis.

Still, it’s impossible to write down all exceptions, which means that sometimes I still break my rules and sometimes the rules break down completely. Thus, I need a way to reinstitute them.

Interlude: guilt

When a rule / productivity system breaks and you start wasting your time, don’t take it too personally and try not to blame yourself. The only thing you can do now is write your observations down, think about how to improve them for the future, and then try to implement them.

Rules stopped working. What next?

First of all, an important qualification: rules don’t just stop working. They stop working in specific contexts, e.g. if you go to a novel location, you will find that the old patterns of behavior — whether productive or destructive — are much weakened there. This suggests a natural solution to the problem of reinstating broken rules: go to an unexplored coffee shop or library and work there until the new location breaks down. Often, people work in libraries and coffee shops precisely for this reason — because these locations allow to create a novel self-pattern specifically for them. The problem with this is that if there are too many possible locations, there’s no incentive to maintain the rules structure in them, so they break down too fast.

I found that I have 3-4 places in town I especially like and rotate my work between those in which rules work at the moment (the rule following ability seems to reset naturally within several days-weeks-months for each location). I have one specific place in which the rules are extra strict, meaning, upon entering this place I turn off mobile internet on the phone and can only turn it on after a 5 minute timer.

Pro tip: you don’t usually go from 0 procrastination to 100 in an instant. If you learn to recognize when you’re at 20 and switch the location preemptively you will save yourself a lot of time.

Physical place is not the only context that can be broken. For example, if you have trouble playing games on your phone everywhere, buying a new one and committing not to play any games on it from the very start can work very well (at least for some time).

Bullshit test for the previous section

The previous section is exceptional in that you can test whether what I wrote there is bullshit rather easily (this is basically the same thing as in the beginning of this post):

- Think of a task you’re currently putting off, even though you shouldn’t.

- Open Google Maps and find a particular coffee shop/library/etc. you’ve never been to.

- Go to that place strongly committing to only doing the particular thing you decided to do there and not get distracted either physically or mentally on other things. This means as little chatting with people as possible; no checking email (unless it’s absolutely needed); no checking social media; not doing anything at all that is not directly related to the task at hand. Basically, maintaining the rule structure similar to the one I described in the beginning of the post.

- Notice how easy or difficult the task was to work on and how easy or difficult it was to not let yourself be distracted, compared to your usual environment.

My prediction: however off-putting and ughy the task is, there’s going to be close to none difficulty in concentrating on it and there will be no other issues that usually prevent you from accomplishing it.

Break rules sometimes

Adhere to anything religiously enough and you start to forget why you decided on doing it in the first place. With rules turning into Chesterton’s fences. Stoics suggest negative visualization and occasional intentional deprivation of things we take for granted, e.g. living off bread and milk for a few days; I suggest to occasionally forget all the rules you have for a while and see what happens. This will happen naturally at some rate, due to rules being gradually broken, but sometimes it might be worthwhile to explicitly let yourself not be bound by any rules designed to enhance productivity and see how it pans out. It seems that this kind of experience may serve as a sort of a springboard for the future.

For example, a couple of times per year I clear out several days, during which I play Civilization 5 for 16-18 hours a day. At some point, I become so nauseated and frustrated by the game that I naturally just can’t play it anymore. The realization of just how easily I just sent like 50 hours of my life down the drain helps to gain the perspective on a lot of stuff, including why I avoid video games so scrupulously at all other times.

Note that spending a day procrastinating / playing video games is equivalent to reading a book for an hour every day for two weeks.

A couple more tips

How to not forget about productivity tricks?

You can literally just add a reminder a week / a month in the future which asks if the new productivity trick is used and, if not, why. I use Amazing Marvin as my todo list and add the reminders there.

Podcasts and audiobooks

If you think you can’t listen to podcasts and audiobooks, you’re probably wrong. Just speed them up and you’ll be able to concentrate on them just fine. You probably have at least 30-60 minutes of downtime every day available for audio content. That’s basically a free hour a day to read a book. The other possibility is that you’ve just tried to listen to a wrong book and gave up too early! I found that about half the books I can’t listen and need to actually read.

The way to highlight books while listening to them is to catch an identifying phrase near the segment you want to return to, write it down to a special file, and after having finished the book, open the written version of the book and find all the highlights there, using the identifying phrases.

See my audio content apps recommendations and headphones recommendations in my Tools / Gear post.

Figuring out the core issues behind procrastination

I will quote Marco Vega of Sapien here:

99% of the time procrastination is not about you being lazy or lacking work-ethic. Your body/brain is sending your some important information about the tasks at hand, and it’s important that you listen to those signals empathetically.

For example,

A - The task requirements and goals might not be clear enough. If you are trying to get yourself to “plan for a project” or “write a book” then it’s hard to identify the next actionable items. Put some time aside to figure out what physical things you can do to move the project forward. Try break down the larger tasks into the smallest pieces possible. The goal of the project might need identifying, or the requirements fleshed out from a supervisor.

B - The task might exceed your current competency. Sometimes we know what we have to do, but don’t know how to do it, and then we become avoidant rather than admitting this. In this case, it’s worth figuring out what you do know how to do and what you don’t know how to do, and be honest with that. Then slowly ask for help or read up on the things you don’t know.

C - The tasks might really not be worth it. Sometimes you are assigned tasks that don’t actually help you achieve your long-term goals, and so your brain demotivate you from doing them. Maybe the payoff is low, maybe you don’t learn anything new from them, or maybe a colleague you don’t like will gain credit for the tasks, or maybe you just wont be rewarded or appreciated for getting the tasks done.

As a general rule of thumb. If you notice yourself procrastinating, don’t beat yourself up about it. Just notice the behaviour and put some time aside to have an honest conversation with yourself for why you might be unconsciously avoiding these tasks. There is no shame here. It’s very difficult to move forward without self-empathy and self-understanding. ‘Pushing yourself’ is OK in small doses, but if you make it a habit, you are increasing your chances of burnout!

Task order

If you just have a bunch of things to do for the day, try using random.org to decide on the order of your tasks. This both

- doesn’t allow you to just do the easiest tasks first

- makes the very act of choosing the next task pretty exciting

Help me make this post better!

If you’ve read to this point, I would guess you enjoyed the post. If you decide to try any of the tricks I describe — do let me know, so that I check back with you in 1, 3, and 12 months and see if this post is actually helpful in the long-term.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Anastasia Kuptsova for many helpful comments.

Also see

Productivity by Sam Altman

Bibliography

Many people influenced my thinking on productivity. In particular, I should note:

Scott Adams’ How to Fail at Almost Everything and Still Win Big (probably the most important book I’ve ever read)

Scott Alexander’s The Lottery of Fascinations

David Allen’s Getting Things Done

Tiago Forte’s The Holy Grail of Self-Improvement

Malcolm Ocean’s A ritual to upgrade my Face

Roko’s Ugh fields

Adam Strandberg’s Time Depletion

Between ages fourteen and sixteen I read a lot of Scott H Young and Tynan and some Steve Pavlina, so although I don’t remember almost anything they wrote, I’m pretty sure there are some traces of their ideas in me.

Stuff with similar thoughts I discovered while writing this post

Peter Hurford’s How I Am Productive

Scott Alexander’s Applied Picoeconomics

Eliezer Yudkowsky’s Execute by Default