Research Ideas

created: ; modified:Also see Patrick Collison's Questions, Gwern's Open Questions, James Ough's research ideas

This is a list of the research I would do / fund if I had more time / money. Do let me know if you find this helpful, have any comments, or know answers to any of these questions!

Does poor eyesight make you smarter?

We know that losing one sense makes you better at others [1, 2, 3, 4]. For example, losing eyesight improves hearing. Why? Apparently, (in the event of blindness) the brain rewires itself and uses the visual areas as auditory ones [3]:

Vision is such an important sense for humans that a huge portion of the brain is devoted to visual processing—far more gray matter than is dedicated to any other sense. In blind people all this brain power would go to waste, but somehow an unsighted person’s brain rewires itself to connect auditory regions of the brain to the visual cortex.

…

Nerves from muscles that control our eye movements, for example, connect to the brain’s hearing centers as well. These connections between visual and auditory regions of the brain become strengthened after losing sight. Also, some regions of cerebral cortex that border visual and auditory cortices—the left fusiform gyrus, for example—expand territory in blind people to make use of the idle circuitry in visual cortex.

Well, why make this a dichotomy? It seems natural, that losing some eyesight during the critical period (i.e. childhood myopia), if left uncorrected, would cause some of the changes that we encounter in fully blind people. We already observe how the brain changes itself during the process of learning to read [5, 6, 7, 8, 9]!

Why do we lose vision in the first place? Many hypotheses, but one I like the most: being inside. So, a child likes reading –> spends time inside, instead of playing outside –> eyesight deteriorates –> parts of the visual cortex rewire themselves to other areas

Books enter the scene

What are books (especially fictional)? They’re essentially a tool that translates persistent visual deprivation into narrative-driven visual hallucinations. So we would expect that the visual neurons get recruited in the parts of the brain responding to “imagination”.

Predictions that this hypothesis generates:

- We would see this effect in people who spent non-trivial parts of their childhood having myopia and not wearing glasses.

- People who start wearing glasses after spending non-trivial parts of their life having myopia and not wearing glasses will

- have worse visual acuity, even if corrected with glasses [9]

- have better other sensory abilities

How does mental imagery work? How do we improve its function?

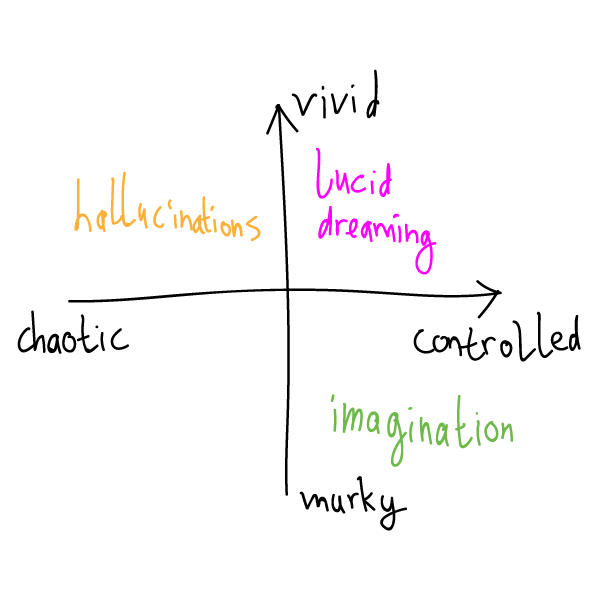

- How do we make imagination vivid?

- How do we make hallucinations controlled?

- How do we make lucid dreaming as easy to enter as simply imagining something?

To figure this out we would probably need to understand how mental imagery (the mind’s eye functions). I have very little idea where to start, tbh.

- It seems that imagination with closed eyes is more vivid. Why?

- It seems that hypnagogia (pre-sleep hallucinations) is somewhere at the intersection of imagination and hallucination: it’s kind of vivid and can be controlled somewhat

- Are tulpas, in a sense, controlled hallucinations?

- wtf: “Individuals with aphantasia, the lack of mental imagery ability, were as good at mental rotation as other people.”

- “Aphantasic here. I do not “rotate” anything in fact,I try to arrive rationally at the solution of the mental rotation task.”

- “I don’t rotate the shape either. I analyze it, take it apart and rebuild it facing the correct way.”

- “Aphantasic here. I do not “rotate” anything in fact,I try to arrive rationally at the solution of the mental rotation task.”

- visual imagery that occurs during REM sleep is more similar to perception than imagination

People who lose vision sometimes have Visual release hallucinations (Charles Bonnet syndrome). These apparently occur, because of the understimulation of the visual areas of the brain.

CBS allows us to integrate the two questions above:

- CBS suggests that in extreme circumstances this leads to hallucinations

- So does “some loss of vision” result in “something like hallucinations”, i.e. improved imagination?

- And if imagination and hallucination are just opposite ends of the same spectrum, how do walk around it?

What moderates the perception of time? How to change it?

Do people have different levels of self-control or do they just experience temptation differently?

- Self-reported strength of temptations, not state or trait self-control, predict goal attainment (N=107, over 3 months)

- “could it be that you’re not actually foregoing current pleasure for future gains, but that you’re lucky enough to enjoy things in the short run which happen to have a long term payoff?”

- “In both studies, men succumbed to the sexual temptations more than women, and this sex difference emerged because men experienced stronger impulses, not because they exerted less intentional control.” (paper)

- “Do different people really report their happiness in the same way? Maybe not.” (paper)

- “I’ve also wondered if anti-natalists (insofar as they are motivated by negative utilitarianism) are not just more sensitive to life’s minor discomforts. Like, I hear all these stories of people like Benatar sobbing during interviews in response to the mere mention of suffering in the abstract, which suggests to me an almost pathological aversion to pain, where most others are made of, well, sterner stuff.”

- “Patients with insensitivity to pain suspect others of exaggerating their pain and often consider them as “sissies” (Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis)

What makes a good life? How do we study this?

Somebody on tumblr writes:

my anxiety has a loophole that if somebody is else of equally or more uncomfortable I develop the sudden ability to Do The Thing

and

i cant go and ask for more ketchup for myself but if my friend wants more ketchup im out of my seat in a second

Same works for me. If someone is more distressed than me (even if I’m really distressed!), my distress evaporates instantly and I’m fully concentrated on helping the other person.

I believe this is a more general observation: if somebody in your immediate vicinity really needs you, you will not be depressed. This explains why men love war, and a bunch of other stuff.

Note, that this doesn’t work if some abstract poor people somewhere need you!

What do we know about happiness today?

Not much. The academic literature seems to be mostly based on surveys which ask people how happy they are. This seems like an exceptionally bad way to study happiness.

Non-academic literature suggests that maybe happiness either stays constant [1, 2] or declines [3], as civilization progresses.

Many people lack intuitive grasp of numbers. How can we help them?

If you interact a lot with random people (not just your relatives, friends, classmates or co-workers), you might have noticed the absence of intuitive sense of numbers. Robin Hanson noticed this when he moved to GMU. Nick Huntington-Klein noticed this when he started doing freelance statistical consulting.

This is probably at least part of the reason for why people stay poor while working full-time jobs; get into huge debts and can’t come out of them; think that 32% of Democrats are LGBT and 38% of Republicans earn >$250,000 per year; why science today is unable to make people save.

In the same vein, Why do many older people struggle with computers? What can younger people do to help?

Is there a tradeoff between episodic and associative memory?

Extraverted people seem to have better episodic memory, e.g. helping them in small talk, while intraverts have better associative memory, helping them to think globally. Is this observation valid? If yes, is there a fundamental tradeoff?

Does learning under alcohol influence occur if you forget whatever happened the last night?

How do the players (game theory) get to know their payoffs?

- Preference Discovery by Jason Delaney, Sarah Jacobson, and Thorsten Moenig

- “We’re writing up a manuscript I’m pretty excited about, except it has inspired some feminist ranting on a pretty fundamental concept in decision making: “exploration”. A basic premise in decision making is you explore the values of options, then you choose the best option.” (perma)

What’s up with our memory of dreams?

We remember dreams almost perfectly right after waking up and then the memory rapidly recedes and disappears completely, unless we write them down. This isn’t how normal memories function. So, why the difference?

Richard Mason emails his thoughts:

Although the phenomenon you mention is at least partly real (we have genuine memories of dreams, which we then forget), I suspect it might also be partly delusional, i.e., I wake up with the conviction that I dreamed a whole novel, but when I try to piece it together, I only have a couple of scenes. It may be, not that all the other chapters were written and then slipped from my memory, but that the chapters were never written in the first place and I only deluded myself into thinking I had a whole book.

What does GDP value? How can we do better?

It seems that what GDP chiefly captures is how much consumer surplus were companies able to capture. What would be a better measure?

Comments

Drake Thomas writes:

Point 4: the quoted reddit comment referring to Benatar is actually misremembering a reference to a Parfit interview (who AFAIK is not a negative utilitarian).

Point 6: The Cognitive Reflection Test seems like a relevant datapoint on ability to do something like “do the math instead of trusting your gut”, a task which is reliably failed even by MIT/Harvard students and gets even more abysmal among less prestigious universities: https://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/pdf/10.1257/089533005775196732. (And the paper didn’t even try a truly representative sample of the population - who knows how low scores would be!) So we have the unfortunate combination of “poor intuitive sense of numbers” and “lack of willingness to challenge intuitions”.

Point 8: I’ve found that drug-induced inhibition of memories can be overcome deliberately with the right techniques. For years beforehand, I recited a certain fictional scenario in my mind, always pausing when I opened a box in the false memory, so that the whole scene was ingrained in long-term memory.

While under memory-suppressing drugs for a wisdom tooth extraction, I reviewed the memory while filling the box with a visual scene as a mnemonic for my experience at the time, bypassing the usual short-term to long-term memory pathway. I remember nothing from a minute after the IV went in until I walked out of the operating room, but the scene is still preserved.

This suggests that most temporary memory inhibition from drugs might only act on the transformation of short-term memories into long-term memories, though of course more experiments would be worthwhile. (I don’t regularly get access to such states, so I haven’t had a chance to try and replicate this effect more rigorously.)

Point 10: I disagree with Richard Mason, having spent some time keeping a dream journal. After a consistent week or two of writing down dreams immediately upon waking, recollection becomes dramatically easier and more reliable, as long as one makes a point of putting pen to paper (or finger to keyboard) within a minute of waking up. It’s easy to fill up a page of details about the dream in pretty exacting detail, in a way that feels much more like true recollection than confabulation. Perhaps dreams of having written a whole novel are false (I’ve never had any such perceived detail), but I do think there’s quite a bit involved in dreams, and the fragments we typically retain an hour later really are less than 5% of what we experienced. (Interestingly, I think the erasure effect seems to act on the contents of the dream a little past sleep - even when I write down the dream, I can come back to the written account a while later and not remember writing the words.)

Thanks to Guy Wilson for making me write this post.