Contra Scott Alexander's "The Tails Coming Apart as Metaphor for Life"

created: ; modified:Happiness

Scott Alexander writes:

Happiness must be the same way. It’s an amalgam between a bunch of correlated properties like your subjective well-being at any given moment, and the amount of positive emotions you feel, and how meaningful your life is, et cetera. And each of those correlated is also an amalgam, and so on to infinity. [emphasis mine]

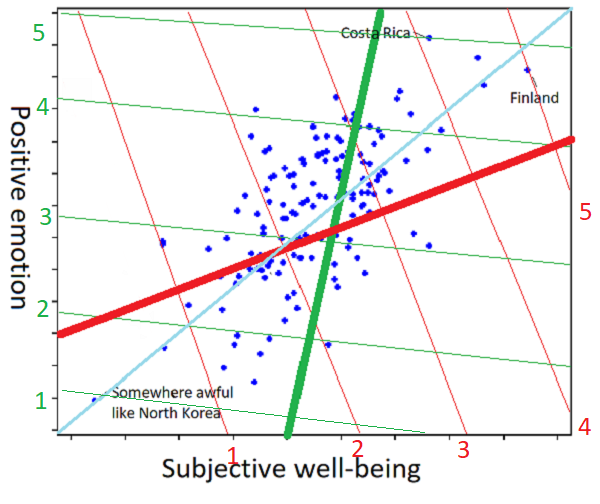

And provides the following diagram:

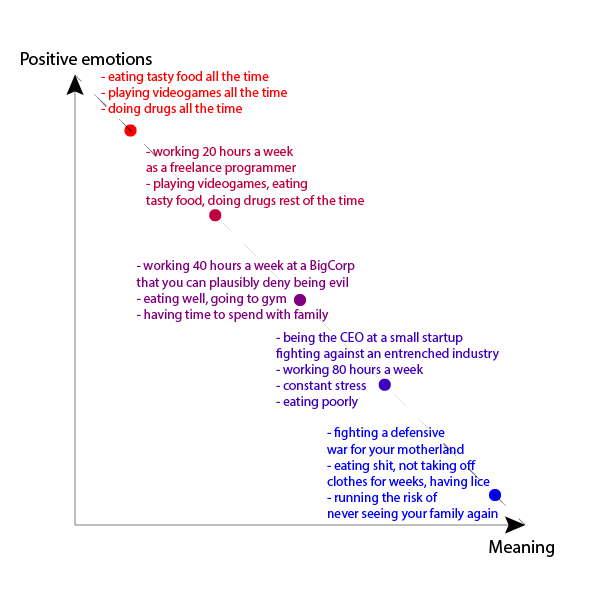

In fact, positive emotions and meaning are negatively correlated.

Why so? Well, what constitutes the most meaningful life? Constantly fighting immense adversities in pursuit of an important goal. And it’s not just the tails: for a unit increase in meaning you have to give up a unit of positive emotion — they are perfectly negatively correlated.

See what the CEO of CircleUp says:

I feel the soul crushing stress and pressure of being a venture backed CEO. In the worst moments – missing a goal, letting a team member go, pivoting - it is almost unbearable. In best moments -just closed round, hired someone amazing, hit big goal- I feel pressure about next.

I feel all consumed. All the time. It’s hard for me to feel present in non-work conversations. On my Friday date night with my wife, I often struggle to focus on us- my mind slips to work. I hate that. I’m embarrassed to admit it. I actively work on it. But I feel all consumed

and yet:

Those moments, and the journey overall, give me so much energy. Because we’re creating something. And the chance to have an impact on others, to help entrepreneurs to thrive, gets me more passionate than I could have ever imagined at work.

Then, there’s war:

War is a brutal, deadly game, but a game, the best there is. And men love games. You can come back from war broken in mind or body, or not come back at all. But if you come back whole you bring with you the knowledge that you have explored regions of your soul that in most men will always remain uncharted.

“What people can’t understand,” Hiers said, gently picking up each tiny rabbit and placing it in the nest, “is how much fun Vietnam was. I loved it. I loved it, and I can’t tell anybody.”

Hiers loved war. And as I drove back from Vermont in a blizzard, my children asleep in the back of the car, I had to admit that for all these years I also had loved it, and more than I knew. I hated war, too. Ask me, ask any man who has been to war about his experience, and chances are we’ll say we don’t want to talk about it–implying that we hated it so much, it was so terrible, that we would rather leave it buried. And it is no mystery why men hate war. War is ugly, horrible, evil, and it is reasonable for men to hate all that. But I believe that most men who have been to war would have to admit, if they are honest, that somewhere inside themselves they loved it too, loved it as much as anything that has happened to them before or since. And how do you explain that to your wife, your children, your parents, or your friends?

How do you even put this on this diagram? I imagine the scene:

“well, two of my buddies were killed today; I killed my first gook; saw a bunch of women raped and houses burned down”

writes down positive emotion: 3, meaning: 7

And even if we try, the diagram will come out like this:

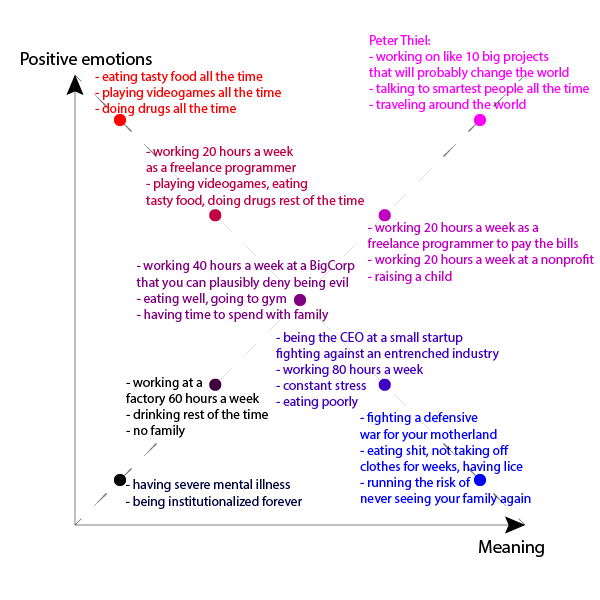

We can try harder and think of more situations:

So, according to this last picture, there’s no tradeoff at all. You can find something incredibly meaningful while still greatly enjoying the life.

What’s the correct answer? Is there a positive correlation with tails coming apart? Is there negative correlation? Is there no correlation at all?

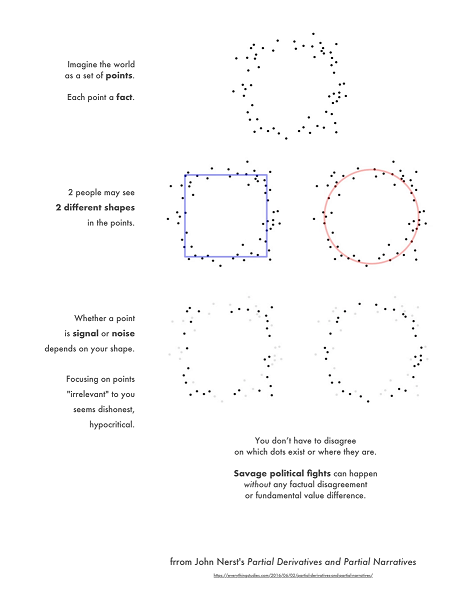

I think the problem is (assuming we can neatly categorize extreme experiences like war) that we can’t really survey the whole space of ways to live one’s life. There are probably a ton of points all over the diagram and in the end we will look at those that fit our preferred narrative the best. This point is illustrated greatly by Eli Parra:

Ethics

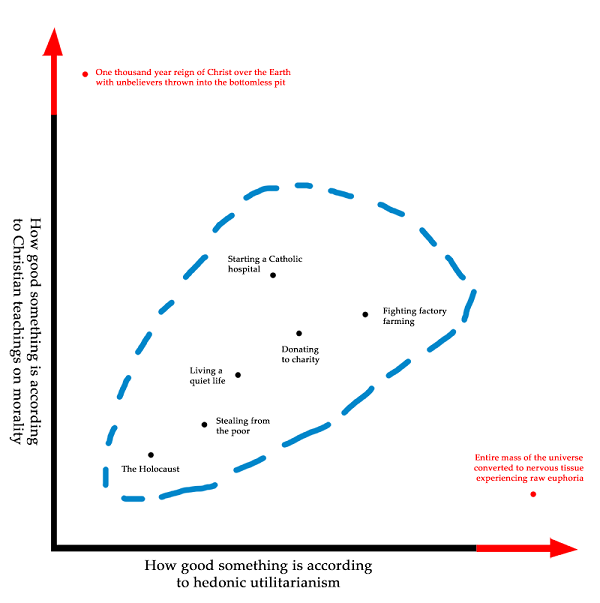

Next, Alexander discusses ethics. He has the following diagram for us:

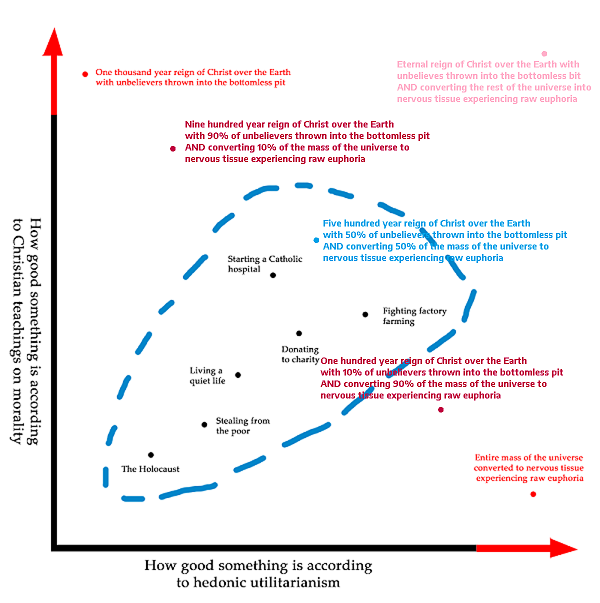

What if we try to augment it a little bit?

Of course this new diagram doesn’t make any sense. But does it make less sense than the original diagram from the post?

Conclusion

In the end, it seems that the sloppiness of reasoning results not in just a worse approximation towards the correct argument, but in an argument that is entirely meaningless and for which you can come up with a diametrically opposed argument (negative correlation between happiness measures / moral actions) of equal plausibility.

See reddit discussion (24 comments) here.

Addendum

This was initially in the main part of the post, but /u/zergling_Lester convinced me that the Commensurability section is bad and /u/UmamiTofu convinced me that the Actions that lack moral weight in Christianity section is bad. I still think that they contain interesting ideas but I no longer think they make good arguments.

Commensurability

Economics has the concept of Lexicographic preferences. Just like any word starting with “A” will come before any word starting with “B” in the dictionary, with lexicographic preferences there exist two goods (say, A and B) such that no positive amount of A can outweigh any positive amount of B.

Christianity has the concept of an Eternal sin, which means that the person who committed any positive amount of eternal sins will have strictly lower goodness than the person who committed zero eternal sins.

Fun fact: lexicographic preferences cannot be reduced to a utility function! This implies that the concept of a real number axis “How good something is according to Christian teachings on morality” doesn’t make sense.

Actions that lack moral weight in Christianity

Utilitarianism assigns moral value to all actions. Going for a walk in the woods when you don’t have to is probably immoral, since you could’ve worked on improving the welfare of people in Africa instead!

A deontological moral system (like Christianity) has a set of rules which say whether some actions are moral or immoral but this set of rules does not extend to all actions. Some actions are left without a moral value. So, if a Christian goes for a walk in the woods, they become neither more nor less good.

Thus, there exist actions which cannot be mapped onto the “How good something is according to Christian teachings on morality” axis at all, again breaking the argument for goodness being correlated / being able to compare goodness of actions in Christianity / Utilitarianism.