Ideas not mattering is a psyop

created: ; modified:By Stephen Malina, Alexey Guzey, Leopold Aschenbrenner.

Introduction

Conventional startup and business wisdom has become “there are plenty of good ideas, all that matters is execution.” We don’t buy it.

Empirically, all our aspiring founder friends are desperate for startup ideas, with few managing to land on something worthwhile, and all our scientist friends are desperate for research ideas.

Good ideas are essential, even ones that seem obvious in retrospect were non-obvious ex ante, and in fact good execution itself depends critically on good ideas.

It’s easy to conflate ideas not guaranteeing success with them not mattering

A common thought-chain you might have when thinking about the importance of ideas for success is:

- Person X had a good idea

- They failed

- Therefore ideas do not guarantee success

- Therefore ideas are not important for success

Steps 1 through 3 are valid. The jump from point 3 to 4 is not. Just because having a good idea does not guarantee success says basically nothing about whether one can succeed without having a good idea.

Startups are hard and if you just naively look at who failed, you’ll see lots of people with good ideas and bad ideas. But it doesn’t follow from this that idea quality doesn’t matter.

For example, suppose it’s 1993 and Bezos is starting Amazon. If he starts with books, his chance of success is 10%. If he starts with cat toys, his chance of success is 1%. Even though having a good idea increased his chances of success by 10 times, the most likely cause of failure is something besides how good his idea is (execution, luck, etc.), which means that for good ideas the most common explanation for startup failure will be about execution, luck, etc. In contrast, startups based on bad ideas will mostly fail because of idea quality.

A similar principle holds in cases where multiple competitors are trying variants of the same idea in parallel. As long as one player doesn’t have a massive head start over the other(s), other factors like execution speed and luck can overwhelm idea quality, despite idea quality mattering a ton.

But can’t you just pivot to a good idea? Yes, if you have a new good idea!

Conclusion: you might want to keep your idea close to you if you are small and need to get a big headstart but you want to tell everyone that ideas don’t matter if you’re a VC or an experienced entrepreneur able to quickly assemble a team and start working on an idea you “found.”

Most people don’t have the experience of getting a good idea nobody ever had

There’s a common adage that “ideas are cheap.” We strongly disagree.

Empirically, all our aspiring founder friends are desperate for startup ideas, with few managing to land on something worthwhile, and all our scientist friends are desperate for research ideas.

Despite us all wanting the world to be fair, meaning that hard work (execution) is the explanation we tend to gravitate towards naturally, having good new ideas that nobody’s ever had is actually very hard, is never guaranteed, and benefits from:

- Knowledge

- Intelligence

- Non-conformity

- Time to think

- Criticism of your ideas

Part of the challenge is that these characteristics are partly in tension with each other. On one hand, developing knowledge clearly benefits from intelligence. But, developing knowledge and being in a position to have time to think both often require learning and succeeding in some institutional context, which can encourage conformity. Learning what other people have thought takes time, which can subtract from spending time generating one’s own ideas. Non-conformity requires ignoring consensus opinions but having your ideas criticized requires listening to people.

You have to enjoy the feeling of insight from having new ideas, but then resign yourself to not coming up with and getting distracted by new ideas until you execute on the existing ones. You have to be highly intelligent and have a thirst for knowledge but not get distracted by insight porn on the internet. You have to be conscientious enough to continue pushing when things inevitably stop being effortless. You have to conform enough to be willing to learn what people have already discovered and accept criticism of your ideas but not conform so much that you squash your creativity or abandon promising ideas prematurely. You have to preserve your time to think in the short term while succeeding enough to stay “in the game.”

Because being powerful and busy often means you lack 4 & 5 (ask an engineer how often they ignore their manager’s technical advice without telling them) and are discouraged from indulging in 3, your likelihood of having good new ideas is lower. On the other hand, your access to people who may have good ideas only increases the more your influence grows. This means that you can benefit a lot from hearing about good ideas and the best way to hear about good ideas is to convince people that they should share them freely.

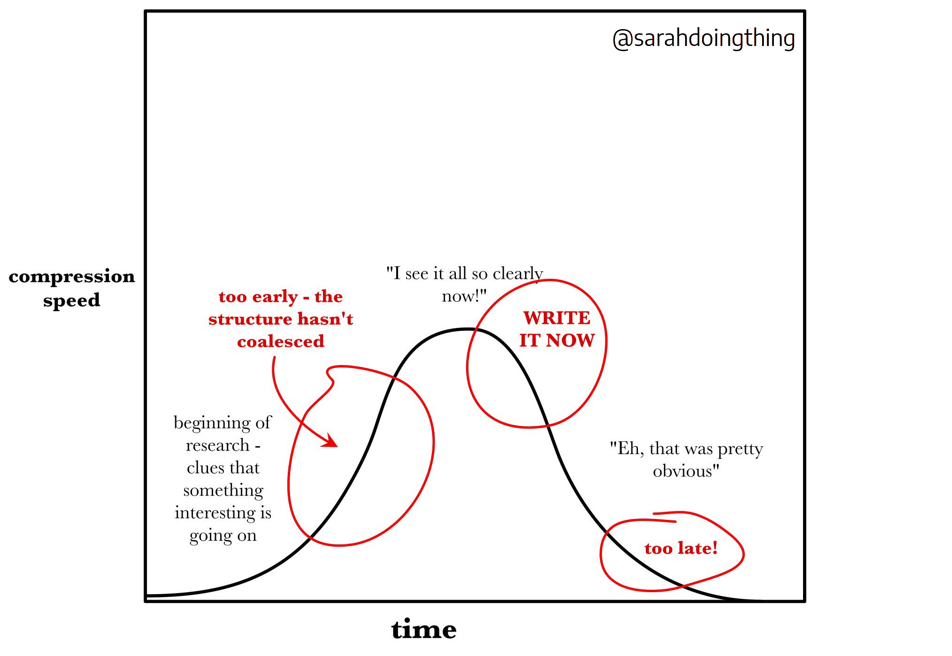

Good ideas often seem obvious in retrospect

When we first went to write this section, Stephen started to write about how obvious Clubhouse was in retrospect. But then when pressed by Alexey, Stephen realized that while live audio on an app might be obvious, the other aspects of Clubhouse’s implementation—rooms, microphone privileges, hand-raising combined with elevation to the stage, innovative privacy violations—are not obvious at all and he could not have come up with them himself.

In the same way most people think they understand how bikes work but cannot come close to drawing a working bike, many of us think we could have generated a seemingly obvious idea when really we would have come up with a version lacking key components that make the actual idea work. Note that it took decades between the introduction of the first bicycles for their designs to stop being utterly ridiculous and to start being actually convenient to use.

Sometimes good ideas really are simple enough that they are actually obvious in retrospect. This still does not mean they were easy to generate! PageRank is mathematically and conceptually simple, yet there were multiple large incumbent search companies who failed to invent it.

It’s extremely easy to forget how confusing or complex something seemed before you understood it. As an example, some of us have had the experience of starting out baffled by computational complexity and then later feeling like the concepts were almost trivial.

Source: @sarahdoingthing.

Good execution depends on good ideas

As these examples—Amazon, Google, Clubhouse—make clear, “execution being the constraint” doesn’t mean “ideas aren’t the constraint.” Even if the broad idea is “obvious” (online store, search engine, audio social media), successful execution requires having good “intermediate ideas” (starting with books for Amazon, PageRank for Google, the implementation details for Clubhouse). The constraint on execution often isn’t something like “operational skill,” but clever ideas about how to make it happen.

This is similar in the academic realm too. In economics, for instance, lots of people were working on “endogenous growth” in the 1980s. The general idea was “obvious.” But Romer still won a Nobel for his R&D-based growth model: he was the one who figured out how to put endogenous growth in a tractable and sound model. Romer won a Nobel for his “execution”—but his execution was good because he had good ideas.

Notes

- Besides the fact that academics are rewarded for idea novelty rather than success, is there something more to their not sharing their ideas? And given that academics are terrified of being scooped, why shouldn’t founders be?

- Academics also don’t share the framework/underlying theses which generate their ideas

- Even when professors will share a lot about what they’re working on, they’ll be more hesitant to tell you how they arrived at their ideas or why they decided to pursue them

- Ideas are often built on top of each other, meaning that credit assignment is genuinely hard, while stealing credit is comparatively easy

- Ideas that do not get written down in a legible form—paper, public blog post—are surprisingly hard to attribute

- Ideas have long feedback loops so it’s hard to validate who is good at having ideas that turn out to be good

- If you have an idea that saves your company $100M in the next 5 years, it’s very unlikely you’ll get even a $5M bonus (assuming that’s not your usual bonus)

- Even if founders think ideas are precious, they have to share them if they want to raise funding, so the observation that founders share their ideas may in part just come from them needing $ and attention

- If you’re reading this bullet, please email me at alexey@guzey.com with the subject line “ideas psyop”.

- In the policy realm, too, lots of people claim that the ideas to fix our various ills are “obvious.” “Just fix zoning laws and the rent wouldn’t be so high,” they say. And yet we don’t implement the supposedly obvious solutions. The constraint is that we don’t have enough good ideas on how to build a coalition to put these policy proposals into practice.

- More ideas that are obvious at a high level but blocked by lacking underlying ideas to make them viable:

- Bitcoin - electronic money obvious, solution to double spend problem non-obvious

- Deep learning slash automatic differentiation obvious. Wait for more powerful GPUs non-obvious.

- The Myth of the Myth of the Lone Genius

Comments

On twitter, @nemozero2 notes:

Generally people are unable to zero-sum their peers in a densely-connected community (e.g. SF tech).

Instead zero-sum concepts like ‘ideas don’t matter’ get laundered through large-scale community norms.

‘ideas don’t matter’ is an attempt by VCs to ‘commoditize their complement’

When ideas don’t matter, the top VCs have a much higher probability of investing in the leading company exploiting the idea

If VCs heavily control the distribution of information to founders (which they do!) then we’d probably expect even more startup wisdom to be tilted in their favor.

Worth considering what other self-beneficial actions in the startup community would make you seem like an asshole.

Gopal Kotecha writes over email:

The emphasis on execution versus idea generation is still justified, but perhaps we should rephrase things to include working on ideas I don’t agree fully with your title (but suspect it is meant to be controversial). I think there are still too many people that worry for too long about ideas. For example, when I told a medical colleague that he should start a company his reply was “I just need the right idea”. The problem with this use of language is that it suggests he has to wait for long enough or perhaps think hard in the bath and one day the idea will just come to him. Instead, what actually happens is that he should go and work on startups in the space he is interested in, figure out what the main pain points are/how people are trying to solve them and then make a bet on the right problem/solution pair (in startups, this is why you need to be able to move fast and break things). Of course related to this is the whole execution side, but even “having an idea” should be phrased as “refining and working on an idea”. We see this in research too - Professors will first half bake an idea that they might mention in a review paper or the discussion section of a relevant experiment and then it gets fleshed out over time.

For students of history, the grand genesis of this blog post: