Matthew Walker's "Why We Sleep" Is Riddled with Scientific and Factual Errors

created: ; modified:Note: I link to a bunch of paywalled studies in this essay. Please do not use sci-hub to access them for free and do not use this trick (a) to easily redirect papers to sci-hub.

For the clearest example of deliberate data manipulation, see how Walker edits out the data that contradicts his argument from the graph.

Also see UC Berkeley’s official response regarding this essay – all problems with the book I discovered are “minor”.

Also see Walker’s post. Note: the post is explicitly not a response to my essay, but rather a response to “questions from readers”. Walker never states any of the points I make and never responds to them directly. I wrote some thoughts on the post here.

Introduction

Matthew Walker (a) is a professor of neuroscience and psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, where he also leads the Center for Human Sleep Science.

His book Why We Sleep (a) was published in September 2017. Part survey of sleep research, part self-help book, it was praised by The New York Times (a), The Guardian (a), and many others. It was named one of NPR’s favorite books of 2017 (a). After publishing the book, Walker gave a TED talk (a), a talk at Google (a), and appeared on Joe Rogan’s (a) and Peter Attia’s (a) podcasts. A month after the book’s publication, he became (a, 2 (a)) a sleep scientist at Google.

On page 8 of the book, Walker writes:

[T]he real evidence that makes clear all of the dangers that befall individuals and societies when sleep becomes short have not been clearly telegraphed to the public … In response, this book is intended to serve as a scientifically accurate intervention addressing this unmet need [emphasis in this quote and in all quotes below mine]

In the process of reading the book and encountering some extraordinary claims about sleep, I decided to compare the facts it presented with the scientific literature. I found that the book consistently overstates the problem of lack of sleep, sometimes egregiously so. It misrepresents basic sleep research and contradicts its own sources.

In one instance, Walker claims that sleeping less than six or seven hours a night doubles one’s risk of cancer – this is not supported by the scientific evidence (Section 1.1). In another instance, Walker seems to have invented a “fact” that the WHO has declared a sleep loss epidemic (Section 4). In yet another instance, he falsely claims that the National Sleep Foundation recommends 8 hours of sleep per night, and then uses this “fact” to falsely claim that two-thirds of people in developed nations sleep less than the “the recommended eight hours of nightly sleep” (Section 5).

Walker’s book has likely wasted thousands of hours of life and worsened the health of people who read it and took its recommendations at face value (Section 7).

The myths created by the book have spread in the popular culture and are being propagated by Walker and by other scientists in academic research. For example, in 2019, Walker published an academic paper that cited Why We Sleep 4 times just on its first page, meaning that he believes that the book abides by the academic, not the pop-science standards of accuracy (Section 14).

Any book of Why We Sleep’s length is bound to contain some factual errors. Therefore, to avoid potential concerns about cherry-picking the few inaccuracies scattered throughout, in this essay, I’m going to highlight the five most egregious scientific and factual errors Walker makes in Chapter 1 of the book. This chapter contains 10 pages and constitutes less than 4% of the book by the total word count.

No, shorter sleep does not imply shorter life span

On page 4, Walker writes:

the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life span

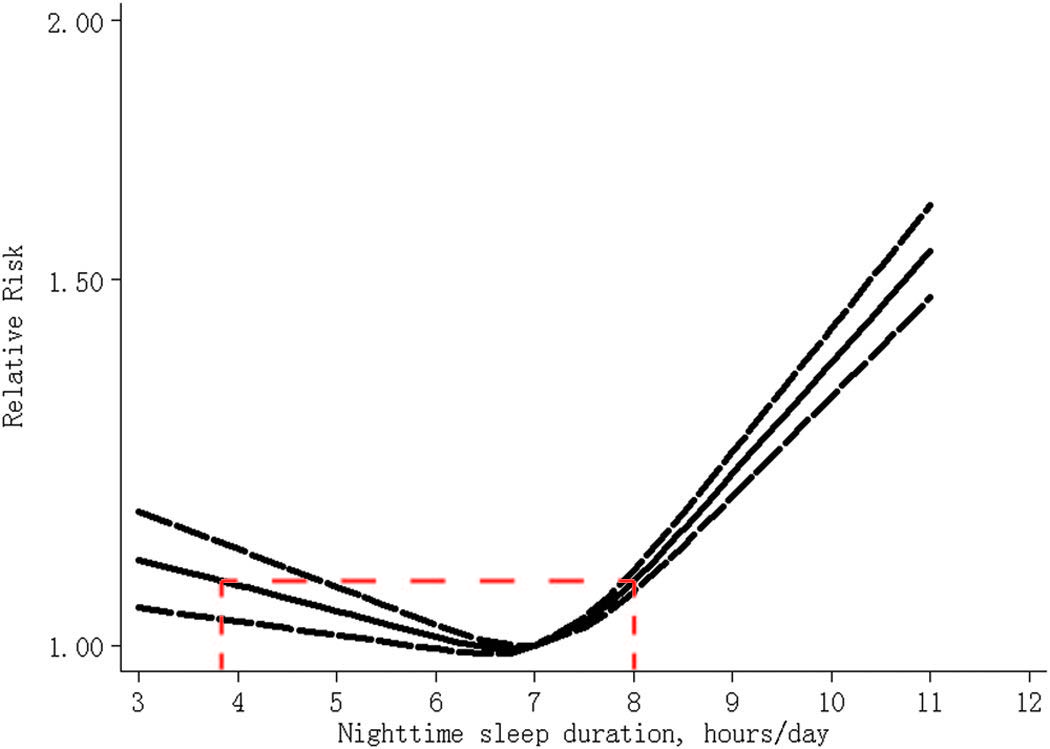

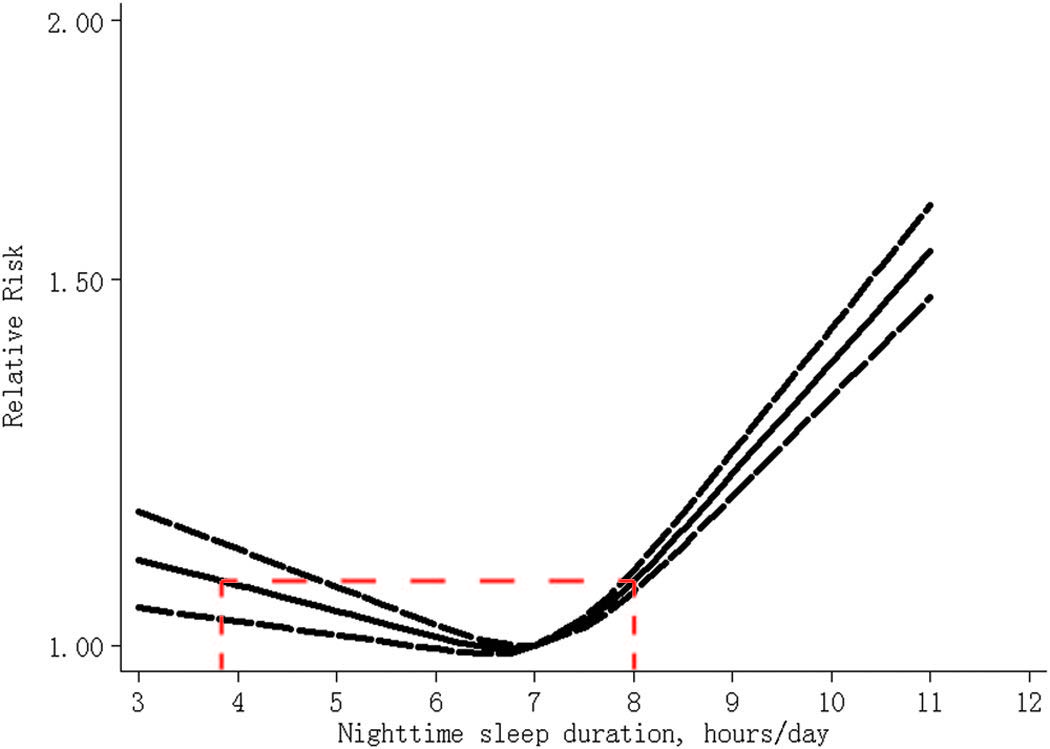

This is false. If you’re concerned about me taking this quote out of context, I provide the full sentence and the two paragraphs leading up to it here. Walker does not cite any studies when making this claim. Most of the studies on the relationship between life span and sleep duration find a U-shaped relationship between length of sleep and longevity, i.e. both short- and long-duration sleep are associated with higher mortality [1 (a) Shen X, Wu Y, Zhang D. Nighttime sleep duration, 24-hour sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality among adults: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 22;6:21480. , 2 (a) Cappuccio FP, D’Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Sleep. 2010 May 1;33(5):585-92. , 3 (a) Kripke DF, Garfinkel L, Wingard DL, Klauber MR, Marler MR. Mortality associated with sleep duration and insomnia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002 Feb 1;59(2):131-6. ]. The studies typically find that people who sleep 7 hours have the highest longevity. Here’s a graph from the first study, published in Scientific Reports in 2016, which performed a meta-analysis of thirty-five prospective cohort studies:

Figure 1. The dose-response analysis between nighttime sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality. The solid line and the long dash line represent the estimated relative risk and its 95% confidence interval. Note: the red dashed line on the graph is mine.

Note that the lowest mortality on the graph is at just below 7 hours and that mortality at 5 hours of sleep per night is basically the same if not lower than mortality at 8 hours of sleep.

As the Encyclopedia of Sleep Kushida C. Encyclopedia of sleep. Academic Press; 2012 Dec 31. – which Walker cites two pages later – notes:

[T]he popular expectation that short sleep is correlated with short life span and long sleep with greater longevity is not supported by the existing literature.

Also, no – sleeping less than 6 hours a night does not double your risk of cancer

On page 3, Walker writes:

Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer.

This is false. Walker does not cite any studies that support this assertion anywhere in the book. There do not appear to exist any experimental studies or studies that would reasonably be able to establish causality, that would support this claim. Even the epidemiological evidence (which you should almost never use to claim causality (a) Even if you “controlled” for confounding variables (a). ) disagrees with Walker’s assertion. For example, a systematic review of sixty-five studies from 2018 (doi), Chen Y, Tan F, Wei L, Li X, Lyu Z, Feng X, Wen Y, Guo L, He J, Dai M, Li N. Sleep duration and the risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis including dose–response relationship. BMC Cancer. 2018 Dec;18(1):1149. which involved 1,550,524 participants and 86,201 cancer cases, found that neither short nor long sleep duration was associated with increased cancer risk.

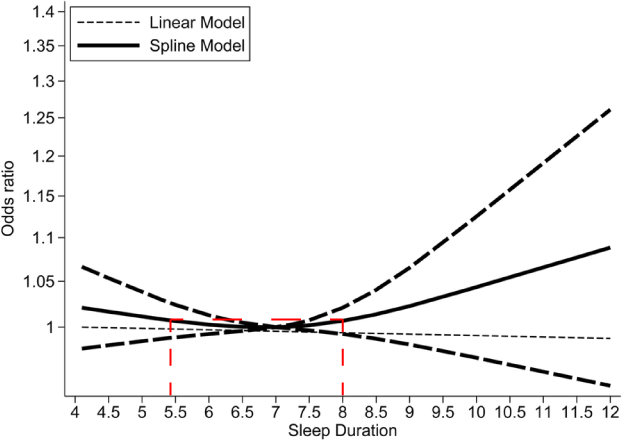

Figure 2. Nonlinear dose–response analyses of sleep duration and cancer risk. The solid line and the long-dashed line represent the estimate odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals. Seven hours of sleep per night was used as the reference Note: the red dashed line on the graph is mine.

How much confidence should we place in epidemiological sleep data?

All of the big studies that are used as inputs for meta-analyses like those I cited above use self-reported data on sleep duration, since it’s impossible to record objective sleep data for a large number of people (this will soon change with the advent of smart watches, bracelets, and rings).

Self-reported data is notoriously unreliable, so it’s not clear how meaningful those studies are, even if all we’re looking for are various correlations. See further discussion of this in Section 12, where I hypothesize that people who have the lowest mortality might actually sleep just 6 hours a day.

No, a good night’s sleep is not always beneficial: sleep deprivation therapy in depression

Note: in this section, I only talk about acute sleep deprivation, i.e. being sleep deprived for one or several days. Chronic or externally imposed sleep deprivation is an entirely different matter and has no relation to sleep deprivation therapy.

On page 8, Walker writes:

[W]e are now forced to wonder whether there are any biological functions that do not benefit by a good night’s sleep. So far, the results of thousands of studies insist that no, there aren’t.

This is false. First, an enormous literature dedicated to the treatment of depression with sleep deprivation has found that people with depression frequently benefit by not getting a good night’s sleep.

Second, Walker directly contradicts himself in Chapter 7 by acknowledging that there are cases when a good night’s sleep is not helpful after all: If you’re concerned about me taking this quote out of context, I provide the full discussion of sleep deprivation therapy in Why We Sleep here.

Approximately 30 to 40 percent of these patients will feel better after a night without sleep … the 60 to 70 percent of patients who do not respond to the sleep deprivation will actually feel worse, deepening their depression. As a result, sleep deprivation is not a realistic or comprehensive therapy option.

In this quote, not only does Walker contradict himself, but he also misrepresents the benefits and the dangers of sleep deprivation therapy. He slightly downplays the number of people who benefit from it – it’s closer to 45-50% if you believe this meta-analysis from 2017 (pdf, a) Boland EM, Rao H, Dinges DF, Smith RV, Goel N, Detre JA, et al. Meta-Analysis of the Antidepressant Effects of Acute Sleep Deprivation. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2017;78(8). or it’s 40-60% if you believe Walker himself from 2009 (doi) Walker MP, van Der Helm E. Overnight therapy? The role of sleep in emotional brain processing. Psychological Bulletin. 2009 Sep;135(5):731. – and he completely mischaracterizes the dangers of it.

In the book, Walker writes that “the 60 to 70 percent of patients who do not respond to the sleep deprivation will actually feel worse, deepening their depression”. However, a review of the literature from 2002 (a) Giedke H, Schwärzler F. Therapeutic use of sleep deprivation in depression. Sleep Medicine Reviews. 2002 Oct 1;6(5):361-77. that he cited in his study from 2009 tells us that depression worsens in less than 10% of patients:

Total sleep deprivation (TSD) for one whole night improves depressive symptoms in 40-60% of treatments. The degree of clinical change spans a continuum from complete remission to worsening (in 2-7%). Other side effects are sleepiness and (hypo-) mania. … It is still unknown how sleep deprivation works.

Here’s a review from 2010 (a): Hemmeter UM, Hemmeter-Spernal J, Krieg JC. Sleep deprivation in depression. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 2010 Jul 1;10(7):1101-15.

The observation that after the recovery night a great majority of SD responders relapse into depression suggests that sleep per se may have a depressiogenic property.

The rapid effect of SD on depressive mood within hours is a fascinating experience for the patient, who may have been depressed for weeks or months …

SD is the only established antidepressant therapy that acts within hours, and therefore, can be applied in patients with treatment-resistant depression with a chance of approximately 50% of seeing an immediate, although temporary, relief from depressive symptoms without major side effects. … The experience of realizing that depression can be lifted and sleep can improve is very important for the further therapy motivation of treatment resistant depressed patients. … [Sleep deprivation] can be combined with antidepressant medication, predominantly serotonergic agents, with bright light therapy and with a phase advance of sleep cycles. All these strategies have been able to provide a chance to stabilize the SD response, at least in a subgroup of patients. [correction: John E. Richters points out that, in 2019, there’s also ketamine (a) which is approved by the FDA for treatment-resistent depression and acts within hours (a).]

Finally, although Walker states that “sleep deprivation is not a realistic or comprehensive therapy option”, a review chapter of sleep deprivation (a) Dallaspezia S, Benedetti F. Sleep Deprivation Therapy for Depression. Sleep, Neuronal Plasticity and Brain Function Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. 2014;:483–502. in the book Sleep, Neuronal Plasticity and Brain Function published in 2014 reads:

[C]onsidering its safety, this technique [sleep deprivation] can now be considered among the first-line antidepressant treatment strategies for patients affected by mood disorders. …

SD is a rapid, safe, and effective therapy for depression. In recent years, this technique has passed the experimental developmental phase and reached the status of affordable clinical intervention for everyday clinical therapy of depressed patients with an increasing literature regarding its safety and efficacy.

This is important because Walker’s scaremongering is likely to harm people with depression who decide to avoid sleep deprivation therapy as a result of reading his book.

Interlude: no, you can't randomly cite 2,000-page-long books and hope nobody will read them

On page 6, Walker writes:

[E]very species studied to date sleeps

This is false, at least, according to Walker’s own source. When making this claim, he cites:

Kushida, C. Encyclopedia of Sleep, Volume 1 (Elsever, [sic] 2013)

….which turns out to be a 2,736 page book that costs $1,995. Fortunately, Walker tells us that we should search for this information somewhere in “Volume 1” or the first 638 pages of the book.

Anyway, page 38 reads:

It now appears that many species reduce sleep for long periods of time under normal conditions and that others do not sleep at all, in the way sleep is conventionally defined.

No, lack of sleep will not outright kill you

On pages 4-5, Walker writes:

[T]here is a very rare genetic disorder that starts with a progressive insomnia, emerging in midlife [fatal familial insomnia (FFI)]. Several months into the disease course, the patient stops sleeping altogether. By this stage, they have started to lose many basic brain and body functions. No drugs that we currently have will help the patient sleep. After twelve to eighteen months of no sleep, the patient will die. Though exceedingly rare, this disorder asserts that a lack of sleep can kill a human being.

This is false. You cannot say that FFI (a) shows that a lack of sleep will kill a human being.

Here is a rough description of the disease: a genetic mutation results in the production of a misfolded protein in the brain, primarily in the thalamus. This protein is toxic to the nerve cells and, over time, it damages the thalamus, resulting in a variety of symptoms, typically including dementia, hallucinations, and insomnia. Eventually, the rest of the brain gets damaged as well, internal organs shut off, the patient’s ability to sleep gets heavily disrupted, and the patient dies.

It is reckless to claim that people with FFI die because of lack of sleep, given the amount of damage across the brain that accumulates in the course of the disease. Accordingly, FFI is considered a neurodegenerative disease. Looking at page 41 of the Encyclopedia of Sleep we discussed in the Interlude:

A disorder called fatal familial insomnia (FFI) is often presented as proof that sleep loss causes death in humans as it does in rats deprived by the forced walking method. However, FFI is a prion disease that affects all body organs and brain cells. There is little evidence that sleep induced by sedation can greatly extend life in FFI patients.

And as one paper notes (a): Schenkein J, Montagna P. Self-management of fatal familial insomnia. Part 2: case report. Medscape General Medicine. 2006;8(3):66.

[T]he prevailing belief [is] that FFI patients ultimately die of neural degeneration

Note that this was Walker’s only example of lack of sleep leading directly to death.

The seven sentences I quoted in the beginning of this section contain (at least) three more scientific errors. See discussion of them in Section 23.

No, the World Health Organization never declared a sleep loss epidemic

On page 4, Walker writes:

[T]he World Health Organization (WHO) has now declared a sleep loss epidemic throughout industrialized nations.

This is false. The WHO never declared a sleep loss epidemic throughout industrialized nations.

In the footnote to this sentence, Walker cites:

Sleepless in America, National Geographic, http://channel.nationalgeographic.com/sleepless-in-america/episode/sleepless-in-america.

One might wonder why he cited a documentary film from National Geographic, rather than the WHO directly, but ok, maybe that film has a reference to the primary source. I watched the entire 88-minute long film twice (official YouTube link Can only be viewed from the US, unfortunately. (a)) to make sure I didn’t miss anything and the film never mentions the WHO or any sleep loss epidemics declared by the WHO and never features anyone from the WHO. I googled:

“world health organization” “sleep loss epidemic”

And didn’t find any documents by WHO. Further, when I restricted the search results to before September 28, 2017 (the date when the book was published), Search results page 1 (a), page 2 (a). I also googled the string ‘“world health organization” “sleep” “epidemic”’ but it didn’t return any relevant results either. the hits either

- used Walker as their source

- never mentioned any sleep loss epidemics declared by the WHO

I discuss the possible origin of this “epidemic” declared by the WHO in Walker’s book here.

Ok, even if the WHO never formally declared any sleep loss epidemics, there still is a global sleep loss epidemic, right?

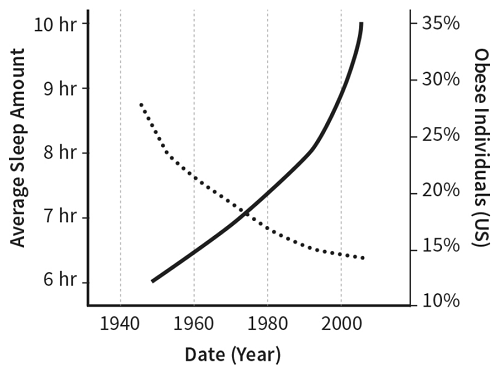

Later in the book (in Chapter 8) Walker provides the following graph that indicates that the average sleep time has decreased by more than 2 hours between 1940s and 2000s and that corroborates his claims of sleep loss epidemic, even if it was not declared by the WHO:

Figure 3. Sleep loss and obesity. Country not specified for sleep data.

I have not been able to find any data that would support the sleep duration numbers Walker provides in the book and it appears that they were simply made up. Further, in a video published by Penguin Books UK in 2019, Walker says:

There’s been a pernicious erosion of sleep time throughout the past 50 years [i.e. between 1969 and 2019]

On the contrary, there’s strong evidence of no reduction in average sleeping time and perhaps even an increase in sleeping time over this approximate time period Bin YS, Marshall NS, Glozier N. Sleeping at the limits: the changing prevalence of short and long sleep durations in 10 countries. American journal of epidemiology. 2013 Apr 15;177(8):826-33. (h/t /u/O2starved) (a):

To investigate whether the prevalences of short and long sleep durations have increased from the 1970s to the 2000s, we analyzed data from repeated cross-sectional surveys of 10 industrialized countries (38 nationally representative time-use surveys; n = 328,018 adults). … Over the periods covered by data, the prevalence of short sleep duration increased in Italy … and Norway … but decreased in Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. … Limited increases in short sleep duration challenge the claim of increasingly sleep-deprived societies. Long sleep duration is more widespread than is short sleep duration. It has become more prevalent and thus should not be overlooked as a potential contributor to ill health.

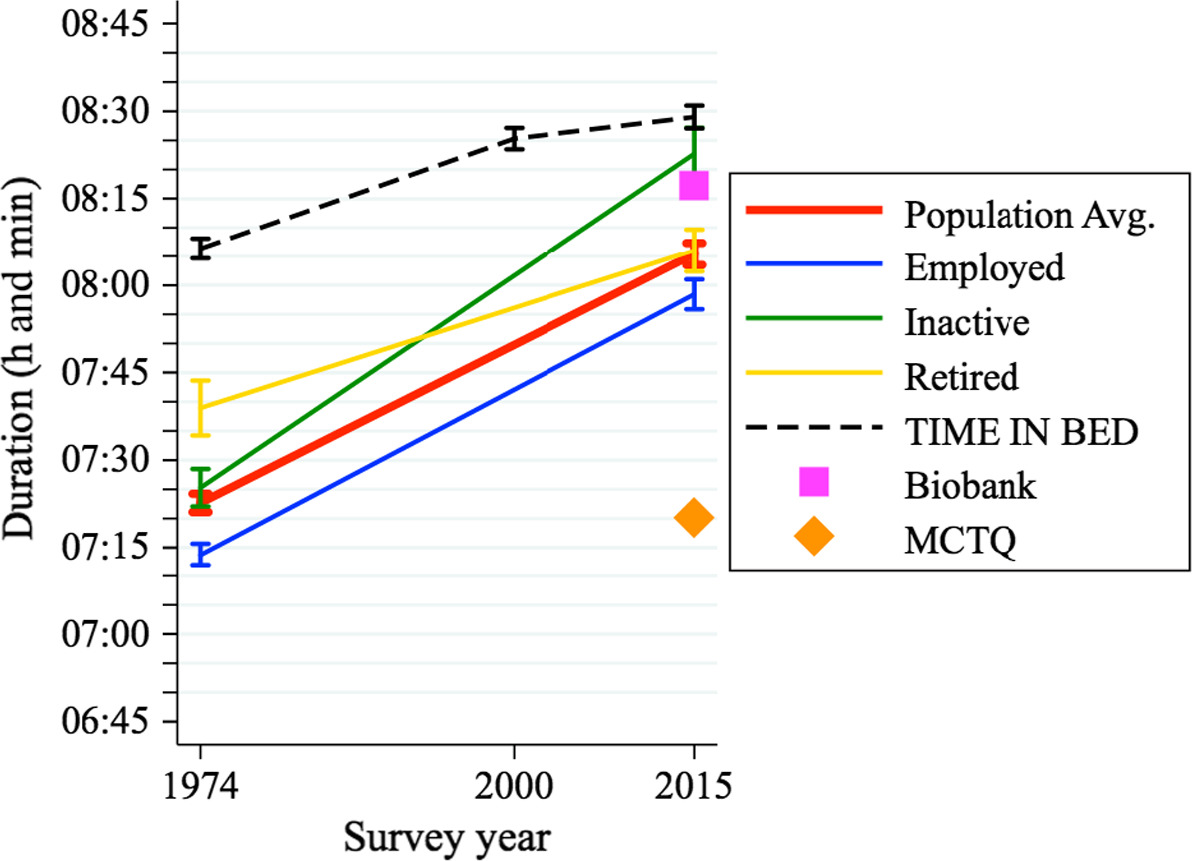

Sleep differences in the UK between 1974 and 2015: Insights from detailed time diaries Lamote de Grignon Pérez J, Gershuny J, Foster R, De Vos M. Sleep differences in the UK between 1974 and 2015: Insights from detailed time diaries. Journal of sleep research. 2019 Feb;28(1):e12753. (a):

It is often stated that sleep deprivation is on the rise, with work suggested as a main cause. However, the evidence for increasing sleep deprivation comes from surveys using habitual sleep questions. An alternative source of information regarding sleep behaviour is time‐use studies. This paper investigates changes in sleep time in the UK using the two British time‐use studies that allow measuring “time in bed not asleep” separately from “actual sleep time”. Based upon the studies presented here, people in the UK sleep today 43 min more than they did in the 1970s because they go to bed earlier (~30 min) and they wake up later (~15 min). The change in sleep duration is driven by night sleep and it is homogeneously distributed across the week. The former results apply to men and women alike, and to individuals of all ages and employment status, including employed individuals, the presumed major victims of the sleep deprivation epidemic and the 24/7 society. In fact, employed individuals have experienced a reduction in short sleeping of almost 4 percentage points, from 14.9% to 11.0%. There has also been a reduction of 15 percentage points in the amount of conflict between workers work time and their sleep time, as measured by the proportion of workers that do some work within their “ideal sleep window” (as defined by their own chronotype).

Figure 4. Average sleep duration and time in bed in the UK between 1974 and 2015 across employment status. From Lamote et al 2018.

No, two-thirds of adults in developed nations do not fail to obtain the recommended amount of sleep

Suppose that you recommend that adults sleep 7-9 hours per night.

- then, someone learns (a) that roughly 40% of people sleep less than 7 hours, roughly 25% sleep 7 hours, and roughly 35% sleep 8 hours or more, meaning that a bit over one-third of people sleep less than you recommend Linked data is for the US but it appears (a) that other developed countries have very similar sleep habits.

- then they look at your recommendation and say that you recommended an average of 8 hours of sleep per night.

- then they say that you recommended 8 hours of sleep per night

- then they say that two-thirds of people sleep less than the 8 hours you recommended

Would this be a fair representation of your position and of the data or would this be misleading?

This is literally what Walker does in his book. On page 3, in the very first paragraph of Chapter 1, Walker writes:

Two-thirds of adults throughout all developed nations fail to obtain the recommended eight hours of nightly sleep.

In the footnote to this sentence he writes:

The World Health Organization and the National Sleep Foundation both stipulate an average of eight hours of sleep per night for adults.

Here are the National Sleep Foundation’s sleep recommendations (a) announced in 2015:

Adults (26-64): Sleep range did not change and remains 7-9 hours

Here are the World Health Organization’s sleep recommendations:

The quote is empty because the WHO does not stipulate how much an adult should sleep anywhere. I don’t know where Walker got this information.

Interlude 2: A decrease of 200—no, 400—no, 600 percent

Is giving three impossible numbers within 200 pages likely to be a coincidence or is it a sign that the writer probably doesn’t know how percentages work?

Chapter 5:

[T]he infants of heavy-drinking mothers showed a 200 percent reduction in this measure of vibrant electrical activity relative to the infants born of non-alcohol-consuming mothers.

Chapter 8:

Deprive a mouse of sleep for just a day, as researchers have done, and the activity of these genes will drop by well over 200 percent.

Chapter 15:

[R]esidents made 400 to 600 percent fewer diagnostic errors to begin with.

As an aside, Walker copy-pasted the 400-600% claim into two of his academic papers published in 2018 and 2019 without noticing that the number doesn’t make sense. See this appendix.

Summary

In the first chapter of Why We Sleep, Walker:

- completely misrepresents the relationship between sleep and longevity and between sleep and cancer (Section 1)

- erroneously states that getting a good night’s sleep is always beneficial (Section 2)

- erroneously states that patients with fatal familial insomnia die because of lack of sleep (Section 3)

- seems to invent a “fact” that the WHO has declared a “sleep loss epidemic” (Section 4)

- misrepresents National Sleep Foundation’s sleep recommendations and uses them to misrepresent the number of adults failing to get the recommended hours of sleep (Section 5)

- also seems to invent the WHO’s sleep recommendations

- calls his book “a scientifically accurate intervention”

Given the density of scientific and factual errors and an apparent invention of new “facts” by Walker, I would caution readers against taking the book’s recommendations at face value.

The potential harm done by the book

Here are some of the potential harms done by the book:

First, Walker’s misrepresentation of sleep deprivation therapy (Section 2) is likely to make many people with depression avoid this potent and largely safe treatment option.

Second, imagine that a 20-year-old who naturally needs to sleep for 7 hours a night, reads Why We Sleep, gets scared, and decides to spend the full 8 hours in bed every day. Then, assuming that they live until 75, they will waste more than 20,000 hours or more than 2 years of their life, with uncertain long-term side-effects.

Finally, to be less speculative, here’s an email from a sleep coach Martin Reed I got after the publication of this essay:

Hello Alexey

I wanted to drop you a line to thank you for all the time and effort involved in debunking Matthew Walker’s book. As someone who works with individuals with insomnia on a daily basis, I know from firsthand experience the harm that Walker’s book is causing.

I have many stories of people who slept well on less than eight hours of sleep, read Walker’s book, tried to get more sleep and this led to more time awake, frustration, worry, sleep-related anxiety, and insomnia. …

Amjad Masad, CEO of repl.it, writes to me:

I’ve had the same experience of developing insomnia as some of the reports you got because I tried to force 8 hours sleep

For more such examples see Section 17.

Conclusion

We have literally no idea about the optimal for long-term health sleep duration. Correction: originally, this sentence read, “as long as you feel good, sleeping anywhere between 5 and 8 hours a night seems basically fine for your health”, but as several people pointed out, ironically, the only support for this statement comes from the correlational data, which I claimed cannot be used to establish causality.

All of the evidence we have about this is in the form of those essentially meaningless correlational studies, but if you’re going to use bad science to guide your sleep habits, at least use accurate bad science.

Figure 1. The dose-response analysis between nighttime sleep duration and risk of all-cause mortality. The solid line and the long dash line represent the estimated relative risk and its 95% confidence interval. Note: the red dashed line on the graph is mine.

Below, I

- explain what I’m not saying in this essay

- explain why people who sleep only 6 hours a day might have the lowest mortality

- explain why I only covered Chapter 1

- explain why Why We Sleep is not pop science and show how it is already creating myths in the academic literature; also I show how Walker copy-pastes academic papers

- cover common objections to the essay (please see them before responding!!!)

- describe my personal experience with sleep

- discuss the concrete harm done by the book

- show how Walker took a graph from the paper and then literally cut out the part of it that contradicted his argument

- list a few interesting emails and messages I received after the publication of this essay

- discuss one paragraph from Chapter 8 that I found especially sloppy

- discuss the mystery of where Walker received his PhD

- discuss a few other things covered in the book

I’m planning to write more about sleep, science in general, and the interpretation of correlational studies in particular. Subscribe, if you’d like to stay updated.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank (in reverse alphabetic order) Misha Yagudin, Brian Timar, José Luis Ricón, Ada Nguyen, Anastasia Kuptsova, Matt Kovacs-Deak, Basil Halperin, Mark Egan, Maxim Efremov, and especially Steve Gadd for reading drafts of this essay. They have improved it immeasurably. All remaining errors are mine.

I would like to thank Kyle Schiller and Adam Canady for the financial support of my writing and research.

Citation

In academic work, please cite this essay as:

Guzey, A. Matthew Walker’s “Why We Sleep” Is Riddled with Scientific and Factual Errors. Guzey.com. 2019 November. Available from https://guzey.com/books/why-we-sleep/.

Or download a BibTeX file here.

Appendix: things I’m not saying in this essay

- sleep is not important

- sleeping well is not important

- people should be sleep-deprived for reasons other than sleep deprivation therapy

- there are no people who naturally need 8 hours of sleep a night

If you believe that I’m saying any of those things, please email me at alexey@guzey.com with a specific passage where I do that. I will fix it.

Appendix: sleep resources that I like

Gregg D. Jacobs’s CBT for Insomnia

Appendix: people who sleep just 6 hours a night might have the lowest mortality

This paper by Lauderdale et al (a) Lauderdale DS, Knutson KL, Yan LL, Liu K, Rathouz PJ. Self-reported and measured sleep duration: how similar are they?. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass.). 2008 Nov;19(6):838-45. is the most well-cited paper on the topic of self-reported vs objectively measured sleep I found. It reads:

the correlation between reported and measured sleep duration was 0.47. Our model suggests that persons sleeping 5 hours over-reported their sleep duration by 1.2 hours, and those sleeping 7 hours over-reported by 0.4 hours.

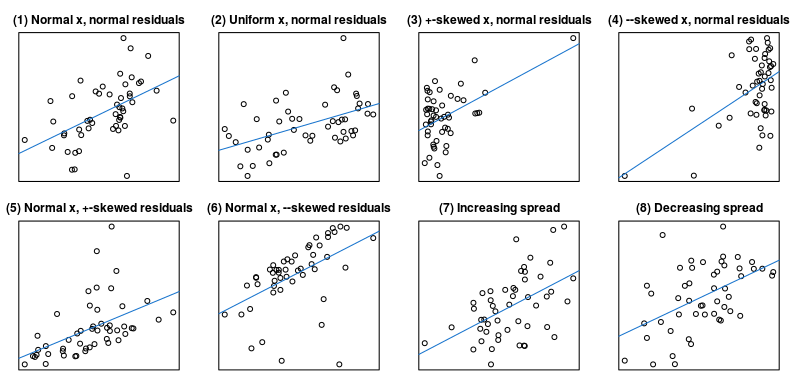

Two other studies I found report a correlation of 0.43 (a) Cespedes EM, Hu FB, Redline S, Rosner B, Alcantara C, Cai J, Hall MH, Loredo JS, Mossavar-Rahmani Y, Ramos AR, Reid KJ. Comparison of Self-Reported Sleep Duration With Actigraphy: Results From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos Sueño Ancillary Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2016 Mar 2;183(6):561-73. and 0.4 (a). Matthews KA, Patel SR, Pantesco EJ, Buysse DJ, Kamarck TW, Lee L, Hall MH. Similarities and differences in estimates of sleep duration by polysomnography, actigraphy, diary, and self-reported habitual sleep in a community sample. Sleep Health. 2018 Feb 1;4(1):96-103. Here’s what a correlation of 0.5 might look like:

This is the kind of noisy sleep data all these big epidemiological studies are based on. Later, Lauderdale et al write:

the average difference at the mean of 6 hours measured sleep was 0.80 hours (48 minutes)

Now, looking at Figure 1, we can see that people who reported sleeping just below 7 hours a night had the lowest mortality. If we interpret this in light of the last quote, people who have the lowest mortality actually sleep 6 hours a night.

One last bit from the Lauderdale et al paper:

The correlation was very low (0.06) for persons with fair or poor self-rated health.

Merijn van de Laar writes:

In appendix 13 you state “if we interpret this in light of the last quote, people who have the lowest mortality actually sleep 6 hours a night”, based on the article by Lauderdale.

I found another article by Manconi [Measuring the error in sleep estimation in normal subjects and in patients with insomnia] (in the attachment) in which it is stated that “normal subjects” do not overestimate their sleep, which is quite contradictory to the Lauderdale article. I dove into it and found out that Lauderdale uses actigraphy to measure objective sleep while Manconi uses polysomnography which is generally thought to be more accurate and thought to better distinguish between stages of sleep and being awake or not, because more indices of sleep are measured (such as EEG). However, in another article comparing PSG and actigraphy, it is mentioned that actigraphy has high sensitivity and accuracy when compared to PSG. So I was still puzzled, until I looked into the characteristics of the participants. The Lauderdale study included only subjects between 18 and 30 years old, while Manconi’s “normal subjects” had an average age of 58.5 (SD 7.23).

A conclusion might be that younger subjects tend to overestimate their sleep, while middle-aged subjects are better in estimating sleep.

Appendix: why I only checked Chapter 1

I spent more than 130 hours over the last 2 months researching and writing this essay (~5 hours to write the outline; ~60 hours to get to the first draft; ~65 hours to edit and fact-check), which constituted essentially all of my surplus free time over this time period. Continuing at the same pace, it would take me more than 3,000 hours to check the entire book. 3,000 hours is the equivalent of 75 weeks or 1.4 years of full-time work.

I hope that going through one full chapter, rather than cherry-picking stuff from across the book, demonstrated the density of errors in the book.

Update a week after the publication (2019-11-22): in the last week, I spent 20 to 30 more hours editing it.

Appendix: is Why We Sleep pop-science or is it an academic book? Also, miscitations, impossible numbers, and Walker copy-pasting papers

Why We Sleep is not just a popular science book. As I note in the introduction, Walker specifically writes that the book is intended to be scientifically accurate:

[T]his book is intended to serve as a scientifically accurate intervention

Consequently, Walker and other researchers are actively citing the book in academic papers, propagating the information contained in it into the academic literature.

Google Scholar indicates that (a), in the 2 years since the book’s publication, it has been cited more than 100 times.

Three papers referring to Why We Sleep

-

A paper (a) Cardon JH, Eide ER, Phillips KL, Showalter MH. Interacting circadian and homeostatic processes with opportunity cost: A mathematical model of sleep with application to two mammalian species. PloS One. 2018 Dec 12;13(12):e0208043. published in PloS One in 2018 reads:

All known forms of animal life must sleep ([1]).

“[1]” here refers to Why We Sleep. If you recall the Interlude, Walker miscites the Encyclopedia of Sleep while making this statement in Why We Sleep.

-

A paper (a) Shallcross AJ, Visvanathan PD, Sperber SH, Duberstein ZT. Waking up to the problem of sleep: Can mindfulness help? A review of theory and evidence for the effects of mindfulness for sleep. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2019 Aug 1;28:37-41. published in Current Opinion in Psychology in 2019 reads:

Chronic sleep disturbance is a global pandemic with two-thirds of individuals failing to obtain the recommended 7–9 h of sleep each night [1].

“[1]” here refers to Why We Sleep. If you recall Section 4 and Section 5, both the “global pandemic” and the “two-thirds” assertions are false.

-

A paper (a) Lyon L. Is an epidemic of sleeplessness increasing the incidence of Alzheimer’s disease?. Brain. 2019 Apr 1;142(6):e30-. published in Brain in 2019 reads:

the World Health Organization has pointed to a ‘global epidemic of sleeplessness’ with roughly two-thirds of adults sleeping less than 8 h a night.

The paper does not cite any sources here and does not cite Why We Sleep anywhere, although the wording strongly suggests that this is where the information originated.

Note also how the papers further miscite Walker and transform his industrialized nations epidemic into a global epidemic. This is how academic urban legends (a) Rekdal OB. Academic urban legends. Social Studies of Science. 2014 Aug;44(4):638-54. are created.

Two papers by Walker citing Why We Sleep

Since Why We Sleep was published, Walker published two academic papers that cited it. Many of the claims in both papers originate from Why We Sleep.

The first one (doi) Walker MP. A sleep prescription for medicine. The Lancet. 2018 Jun 30;391(10140):2598-9. was published in The Lancet in 2018.

The second one (doi) Walker MP. A Societal Sleep Prescription. Neuron. 2019 Aug 21;103(4):559-62. was published in Neuron in 2019. It’s 4 pages long and it references Why We Sleep 7 times.

For example, in The Lancet, Walker writes:

pilot studies have shown that when you limit trainee doctors to no more than a 16 h shift, with at least an 8 h rest opportunity before the next shift, serious medical errors drop by over 20%. Furthermore, residents make 400–600% fewer diagnostic errors to begin with.

In Neuron, Walker writes:

pilot studies have shown that when you limit trainee doctors to no more than a 16-h shift, with at least an 8-h rest opportunity before the next shift, serious medical errors drop by over 20%. Furthermore, residents make 400%–600% fewer diagnostic errors to begin with (Walker, 2017).

And in Why We Sleep, Walker writes:

several pilot studies in the US have shown that when you limit residents to no more than a sixteen-hour shift, with at least an eight-hour rest opportunity before the next shift, the number of serious medical errors made—defined as causing or having the potential to cause harm to a patient—drops by over 20 percent. Furthermore, residents made 400 to 600 percent fewer diagnostic errors to begin with.

Three observations:

- reducing a positive number by 100% brings it to 0. According to Walker, residents who are limited to no more than a 16-h shift, with at least an 8-h rest opportunity before the next shift, make a negative number of mistakes

- note the ability of peer review to detect basic arithmetic mistakes

- the quoted statistics from Why We Sleep are unsourced and we have no way to see how or where Walker got these numbers. Via The Lancet and Neuron, they have have now entered the scientific literature, while lacking a primary source

- the wording in The Lancet, Neuron, and in Why We Sleep is extremely similar

Walker copy-pasting papers

Update: the Neuron article was retracted “at the request of the Author”.

To expand on the last point, the last 2 pages of the Neuron paper, appear to be mostly identical to The Lancet paper, this despite Neuron publisher’s policy being (a):

Manuscripts are considered for publication with the understanding that no part of the work has been published previously in print or electronic format

Figure 6. The Lancet paper is on the left. Neuron paper is on the right. Identical text is highlighted in red. Image created with the help of copyleaks.com

Further reading

Appendix: discussion

See discussion of this essay on the forum, Hacker News (a), Marginal Revolution (a), Andrew Gelman’s blog 1 (a), 2 (a), 3 (a), 4 (a), /r/slatestarcodex (a), Twitter (a), listen to BBC interviewing me and Walker himself about it or listen to my interview with Smart People Podcast discussing it.

Appendix: common objections

1. "Walker is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Berkeley who spent more than 20 years studying sleep. Who the fuck are you?"

I’m Alexey. You’re welcome.

On a more serious note, I have a BSc in Mathematics and Economics. During my undergrad, I took 2 years of statistics, a year of econometrics and worked as a research assistant for an economics prof for about 3 years. I also took graduate-level psychology, neuroscience, and biology courses. Over the last several years, I spent many hundreds of hours studying biology and neuroscience.

Since the publication of this essay, it was read by hundreds of psychologists and neuroscientists who–I believe–also failed to find any serious issues. Regardless of what I believe, you can check the discussions in the links in the beginning of the essay and check whether this is true for yourself.

Some of the scientists wrote to me directly. Here’s a sleep scientist with >50 h-index who studied sleep for more than 40 years:

Hello Alexey,

I thoroughly enjoyed your review of Walker’s sleep book. I myself am a sleep researcher but - I would like to think - of quite a different ilk from the Walker variety. In fact, I was so infuriated by the Walker claims that I bought a copy of the book so that I could review it. Upon receipt of the Kindle edition, I found it so full of falsehoods, lightly tossed out, that I didn’t know where to start. Your decision to limit your comments to the first chapter was a great solution to what could have become an intractable morass.

2. "The mortality/sleep J-curve from section 1 doesn't disprove Walker's 'the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life span'. First, the association between long sleep and short life span is generally considered to reflect underlying comorbidities that prolong time in bed. Second, this doesn't look at sleep loss or sleep extension at the level of the individual person and if you look at the individual person, then shorter sleep is likely to be associated with shorter life."

(argument adapted from this video, time 7:13, and from many other people making versions of it)

First, it is true that some diseases lead to prolonged sleep. However, some diseases also lead to shortened sleep. For example, many stroke patients suffer from insomnia (a) Sterr A, Kuhn M, Nissen C, Ettine D, Funk S, Feige B, Umarova R, Urbach H, Weiller C, Riemann D. Post-stroke insomnia in community-dwelling patients with chronic motor stroke: physiological evidence and implications for stroke care. Scientific Reports. 2018 May 30;8(1):8409. and people with fatal familial insomnia struggle with insomnia. Therefore, if you want to make the argument that the association between longer sleep and higher mortality is not indicative of effect of sleep, you have to accept that the same is true about shorter sleep and higher mortality. As Cappuccio et al 2010 (cited in section 1) note, these associations do not have a single accepted reason behind them:

Proposed mechanisms for mortality associated with long sleep include: (I) long sleep is linked to increased sleep fragmentation that is associated with a number of negative health outcomes; (II) long sleep is associated with feelings of fatigue and lethargy that may decrease resistance to stress and disease; (III) changes in cytokine levels associated with long sleep increase mortality risk; (IV) long sleepers experience a shorter photoperiod that could increase the risk of death in mammalian species; (V) a lack of physiological challenge with long sleep decrease longevity; (VI) underlying disease processes mediate the relationship between long sleep and mortality.

Second, at the level of an individual, there do not appear to exist any experimental studies or studies that would reasonably be able to establish causality that would support the claim that sleep restriction cause long-term health problems or an increase in mortality.

You could say that it is well-known that short-term (acute) lack of sleep causes a stress response from the organism. This is true. However, if you make this argument, you should also consider the following argument about the dangers of exercise valid:

When we exercise, our blood pressure and heart rate would increase. Stress hormones’ concentration in the blood rises and the muscles get damaged. Therefore, exercise is bad for your health.

Exercise demonstrates that arguments of the form “x makes me feel bad in the short-term, therefore it’s bad for health” are suspect.

In general, be careful to distinguish short-term stress response and long-term stress response.

3. "Only checking the introduction is wrong because it's not representative of the rest of the book. In later chapters, Walker is much more rigorous."

Please see section 18, section 19, and section 22, where I cover problems with chapters 6 and 8. For example, in section 18, I show how Walker literally cuts out the part of a graph that displays the data in contradiction with his argument.

4. "But don't many people get 8-9 hours of sleep when they don't restrict sleep?"

Many people do seem to need 8-9 hours of sleep.

However, let me make an analogy: when people don’t restrict their food-eating, many of them start eating more than they need and become obese, meaning that simply allowing ourselves to get as much food as we want, likely isn’t the healthiest choice. My guess is that same is likely true for sleep.

5. "In Chapter 1, Walker writes 'vehicular accidents caused by drowsy driving exceed those caused by alcohol and drugs combined'. This shows how dangerous it is to not sleep and you have not refuted this part."

I did look into this. I was not able to find any data on vehicular accidents caused by drowsy driving. However, the data by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration on accidents that involve drowsy driving (a) and that involve drugs and alcohol (a) does not support this assertion.

According to this data, 1.2-1.4% (Table 2 in linked file) of car crashes involved drowsy driving, while 2.8% (Table 7 in linked file) of car crashes involved driving while having the alcohol blood concentration above the legal limit in the US (and this is not including accidents involving drugs).

6. "Ok, maybe sleep and longevity are not positively related, but the part of the book I found most important is about sleep and learning. For example, in Chapter 7, Walker writes that 'a memory retention benefit of between 20 and 40 percent [is] being offered by sleep'. This shows how important sleep is for memory and you have not refuted this part."

I have not investigated Walker’s claims about sleep and learning, since he does not make any concrete statements about this in Chapter 1. However, is there any reason to expect his treatment of sleep and learning to be any more accurate than, for example, his treatment of the relationship between sleep and longevity?

7. "In Chapter 15, Walker writes that 'after a thirty-hour shift without sleep, residents make a whopping 460 percent more diagnostic mistakes in the intensive care unit than when well rested after enough sleep'. This shows how dangerous it is to not sleep and you have not refuted this part."

Is there any reason to expect that this is one statistic he decides to portray accurately? Have you considered looking at the scientific literature and seeing if this number checks out?

Appendix: my personal experience with sleep

Before doing all of this research, I frequently forced myself to sleep 8 hours, even if I naturally woke up after 7. I no longer do that and I continue to experiment with my sleep.

Appendix: the concrete harm done by the book

A sleep physician Daniel Erichsen (a) writes:

Dear Alexey,

Your essay on Why we sleep - I can’t thank you enough. I’m a sleep doctor in Oregon and have seen many many patients who have developed severe sleep anxiety and insomnia. Two friends in the sleep field and myself weekly have talked about people that slept well until reading this book.

This is the email from a sleep coach Martin Reed (a) I quoted in Section 7:

Hello Alexey

I wanted to drop you a line to thank you for all the time and effort involved in debunking Matthew Walker’s book. As someone who works with individuals with insomnia on a daily basis, I know from firsthand experience the harm that Walker’s book is causing.

I have many stories of people who slept well on less than eight hours of sleep, read Walker’s book, tried to get more sleep and this led to more time awake, frustration, worry, sleep-related anxiety, and insomnia.

Martin also linked to this episode (a) of his podcast on insomnia:

Scott slept well his entire life until he listened to a podcast that led him to worry about how much sleep he was getting and the health consequences of insufficient sleep. That night, Scott had a terrible night of sleep and this triggered a vicious cycle of ever-increasing worry about sleep and increasingly worse sleep that lasted for ten months.

SleepyHead (a sleep clinic in Exeter, UK) writes (a):

My patients are coming to me after reading this alarmist book, with insomnia that they did not have before, and worse, harder to treat because although the book has caused these anxieties - they can’t shake their newly built alarmist beliefs they learnt from the very same book.

After a week of forced 8-hour sleep I faced a problem of not falling asleep for more than an hour. It’s odd on the verge of hyper-personalized healthcare to spread one-size-fits-all advice like that.

Appendix: what do you do when a part of the graph contradicts your argument? You cut it out, of course

Note: this problem was first noticed by Olli Haataja

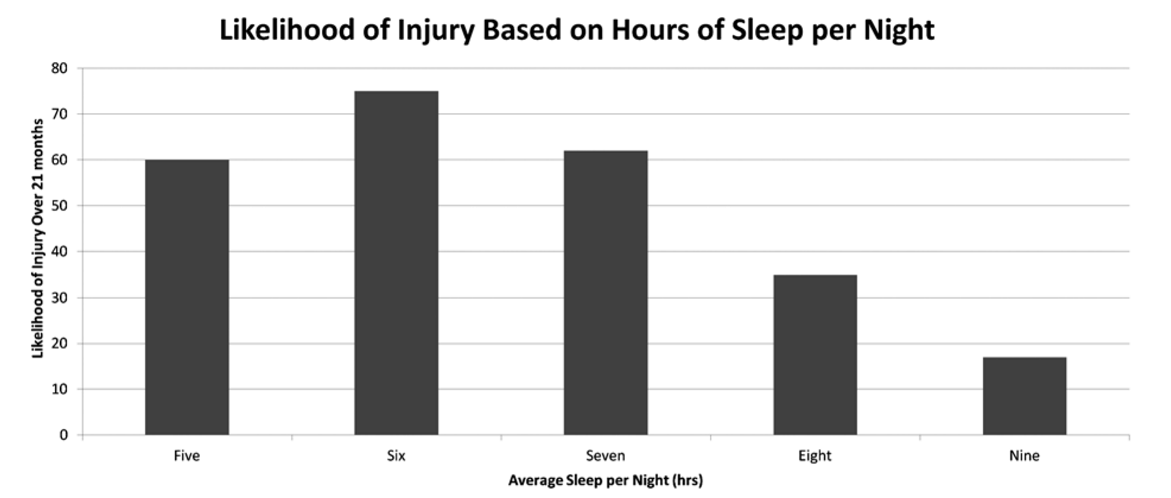

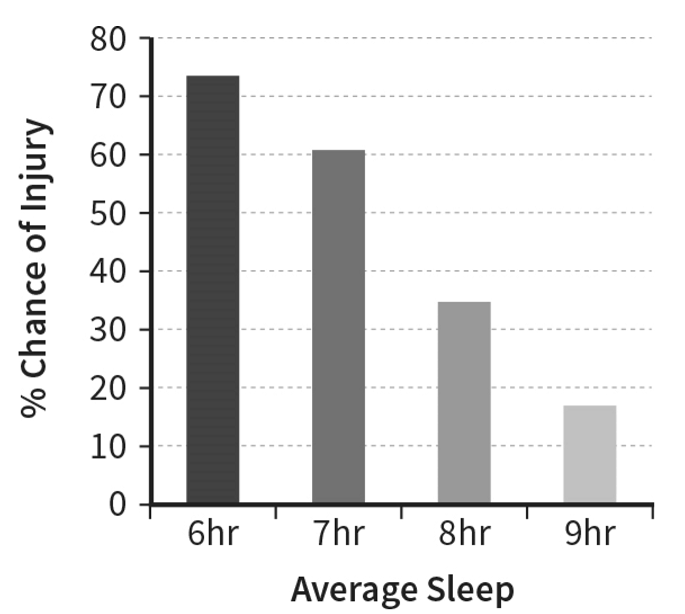

Figure 7. Likelihood of injury over 21-month period based on hours of sleep per night.

This is a graph from the paper called Chronic Lack of Sleep is Associated With Increased Sports Injuries in Adolescent Athletes. Milewski MD, Skaggs DL, Bishop GA, Pace JL, Ibrahim DA, Wren TA, Barzdukas A. Chronic lack of sleep is associated with increased sports injuries in adolescent athletes. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics. 2014 Mar 1;34(2):129-33. Walker cites this paper in Chapter 6 and provides an adaptation of this graph:

Figure 8. Likelihood of injury over 21-month period based on hours of sleep per night.

The 5 hours of sleep column – which is associated with lower chance of injury than 6 hours of sleep – has simply disappeared.

Similarly Walker discusses this study on the Joe Rogan podcast, saying that there’s “a perfect linear relationship: the less sleep that you have, higher your injury risk” in athletes when they were surveyed and found to be sleeping between 4 and 9 hours and that those who slept 5 hours have almost 60% more injuries than those who sleep 9 hours.

Note that none of these facts are true. Nobody slept 4 hours; the relationship is not perfectly linear; and the increase from 9 hours of sleep to 5 hours of sleep is about 230%, not 60%.

As an aside, that 9 hours of sleep column is based on exactly 1 child being injured out of 6 children who reported sleeping for 9 hours.

Many people defend Walker cutting of the data from the graph by saying that he is just trying to make the trend clearer for the popular audience. As I noted in the Introduction of this essay, this argument is indefensible:

On page 8 of the book, Walker writes:

[T]he real evidence that makes clear all of the dangers that befall individuals and societies when sleep becomes short have not been clearly telegraphed to the public … In response, this book is intended to serve as a scientifically accurate intervention addressing this unmet need …

The myths created by the book have spread in the popular culture and are being propagated by Walker and by other scientists in academic research. For example, in 2019, Walker published an academic paper that cited Why We Sleep 4 times just on its first page, meaning that he believes that the book abides by the academic, not the pop-science standards of accuracy (Section 14).

I devote an entire section to the discussion of whether Walker’s book is “pop-science” here.

See discussion of this point by Andrew Gelman: “Why we sleep” data manipulation: A smoking gun? (a)

Update: Neil Stanley shows another example of Walker cutting off data from the graph to change its conclusion (a):

not for the first time! the 1st pic is a tweet from the @sleepdiplomat [a] 15/06/19 [archived tweet] the 2nd data from the paper, he has cropped both the data and the word ‘ratio’ to misrepresent the data which actually shows Veteran suicides peaks between 1000–1200 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S138994571830861X [a]

Appendix: Letters from the readers

Leonardo Tozzi writes in an email:

two of my close friends had stopped sleeping after reading “Why we sleep”, but your post “cured them”. I had tried myself to convince them the book was nonsense but couldn’t.

Appendix: a strong contender for the single most absurd paragraph in the book

In Chapter 8, Walker discusses the relationship between sleep and cardiovascular health. In the first paragraph of this discussion, he mentions two studies. He seems to completely misrepresent both of them. Most notably, in the description of both of these studies he inflates their sample sizes. In one case, the study’s 474,684 people turn into “more than half a million”. In the other case, 2,282 people turn into “over 4,000”.

Here’s what Walker writes:

Unhealthy sleep, unhealthy heart. Simple and true. [1] Take the results of a 2011 study that tracked more than half a million men and women of varied ages, races, and ethnicities across eight different countries. Progressively shorter sleep was associated with a 45 percent increased risk of developing and/or dying from coronary heart disease within seven to twenty-five years from the start of the study. [2] A similar relationship was observed in a Japanese study of over 4,000 male workers. Over a fourteen-year period, those sleeping six hours or less were 400 to 500 percent more likely to suffer one or more cardiac arrests than those sleeping more than six hours. [numeration mine]

Although he does not cite the two studies he discusses, he gives enough identifying information that I believe I was able to find both of them.

The first one is Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies (a). Cappuccio FP, Cooper D, D’elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Sleep duration predicts cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. European Heart Journal. 2011 Feb 7;32(12):1484-92. Here are the characteristics of the paper that match Walker’s description:

- published in 2011

- sample size approximately 500,000

- 8 different countries

- increase in coronary heart disease of approximately 45% in the short sleep duration condition

- follow-up between seven and twenty-five years

Here are the issues with his description of the paper:

- the sample size is 474,684, not “more than half a million”

- Walker writes, “Progressively shorter sleep was associated”, implying that shorter the sleep, the higher the incidence of disease. Instead, the study found that both short and long sleep duration were associated with increased risk of developing or dying from coronary heart disease

- Walker fails to mention that short sleep was not associated with total cardiovascular disease (the statistic we care the most about), while long sleep was positively associated with total cardiovascular disease

The second study he appears to describe in that paragraph is The effects of sleep duration on the incidence of cardiovascular events among middle-aged male workers in Japan (a). Hamazaki Y, Morikawa Y, Nakamura K, Sakurai M, Miura K, Ishizaki M, Kido T, Naruse Y, Suwazono Y, Nakagawa H. The effects of sleep duration on the incidence of cardiovascular events among middle-aged male workers in Japan. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2011 Sep 1:411-7. Here are the characteristics of the paper that match Walker’s description:

- Japanese male workers

- fourteen year follow-up

- 4-5x figure is given for one of the outcomes that resembles cardiac arrests

Here are the issues with his description of the paper:

- the sample size is 2,282 not “over 4,000”

- the entire “those sleeping six hours or less were 400 to 500 percent more likely to suffer one or more cardiac arrests than those sleeping more than six hours” sentence is false (see Table 2 in the paper)

- the association Walker talks about compared those sleeping strictly less than 6 hours to those sleeping between 7 and 7.9 hours, while Walker says that the comparison was between those sleeping 6 hours or less and those sleeping more than 6 hours

- the figure was approximately 4x to 5x, which is the same as an increase of 300 to 400 percent, not 400 to 500 percent

- the paper does not have any statistics about “one or more cardiac arrests”

- the figure Walker mentions is referring to “coronary events” which the paper describes as “myocardial infarction or angina requiring catheter or surgical intervention”, not “cardiac arrests”

- deaths from cardiac arrests were included in “Cardiovascular events” category and were not studied separately

Appendix: where did Walker get his PhD?

I was looking into Matthew Walker a bit and it seems odd that where he claims he got his PhD on his own website [a] (the MRC in London, very prestigious) is clearly not where he got his PhD: both his thesis [a] and wikipedia page [a] show that his PhD was from the University of Newcastle upon Tyne (less prestigious). A contemporaneous publication [a] shows his affiliation as “MRC Neurochemical Pathology Unit, Newcastle General Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK”.

Was he just sloppy in writing up the bio on his own website? Or stretching the truth to tell a better story? This seems reminiscent of the issues that /u/guzey and others are grappling with in this thread.

Matthew Walker’s site says (a):

Dr. Walker earned his degree in neuroscience from Nottingham University, UK, and his PhD in neurophysiology from the Medical Research Council, London, UK.

As of 2019-12-03, the University of Newcastle upon Tyne is never mentioned on Walker’s site (a). I emailed MRC London for a confirmation that Walker received his PhD there and they told me that they do not grant PhD degrees. Neil Stanley notes on twitter (a):

The MRC is not a degree/PhD awarding body. He may have got funding from the MRC for his studies but his PhD must have been awarded by an academic institution.

Appendix: serious problems in Chapter 8 found by a reader

On forum.guzey.com, ish found several more serious problems with Why We Sleep:

Chapter 8 also contains another erroneous description of an existing study. In the section “Sleep Loss and the Reproductive System” Walker refers to work by Tina Sundelin on “how attractive you look when sleep-deprived”. This appears* to refer to the study “Beauty sleep: experimental study on the perceived health and attractiveness of sleep deprived people” (Axelsson, Sundelin, Ingre, Van Someren) [2010] {10.1136/bmj.c6614}.

Walker states that:

In one of the sessions, the participants were given just five hours of sleep before being put in front of the camera, while in the other session, these same individuals got a full eight hours of sleep.

He goes on to say:

The faces pictured after one night of short sleep were rated as looking more fatigued, less healthy, and significantly less attractive.

However, in the cited paper it says that the researchers

photographed the faces of 23 adults (mean age 23, range 18-31 years, 11 women) between 14.00 and 15.00 under two conditions in a balanced design: after a normal night’s sleep (at least eight hours of sleep between 23.00-07.00 and seven hours of wakefulness) and after sleep deprivation (sleep 02.00-07.00 and 31 hours of wakefulness)

Walker completely fails to mention that the individuals who received five hours of sleep were also sleep deprived for 31 hours. This fact is even directly stated in the abstract of the paper:

Participants were photographed after a normal night’s sleep (eight hours) and after sleep deprivation (31 hours of wakefulness after a night of reduced sleep)

This completely changes the interpretation of the paper. Being able to tell visually if someone has had 5 hours of sleep is considerably different from being able to tell if they have had five hours of sleep AND have been sleep deprived for 31 hours.

And in another comment in the same thread, ish writes:

[I]n Chapter 8 in the section “Sleep Loss and the Immune System” he [Walker] refers to work by Dr. Aric Prather regarding sleep and colds. He describes the results of the study (without citation) “Behaviorally Assessed Sleep and Susceptibility to the Common Cold” (Prather, Janicki-Deverts, Hall, Cohen) [2015] {10.5665/sleep.4968}. Walker states that:

“In those sleeping five hours on average, the infection rate was almost 50 percent”.

However, looking at the paper, of the 164 participants (Walker refers to this as “more than 150”) “124 (75.6%) were infected and 48 (29.3%) developed a biologically verified cold”. From page 4, Figure 1 of the paper, ~45% of those who slept LESS than 5 hours developed an objective cold (~16 out of 36 people), while ~30% of those who slept 5-6 hours (16 out of 54 people) developed a cold. So somehow 45% sleeping LESS than 5 hours transforms into 50% sleeping 5 hours ON AVERAGE.

Appendix: fatal familial insomnia

Once more, on pages 4-5, Walker writes:

[T]here is a very rare genetic disorder that starts with a progressive insomnia, emerging in midlife [fatal familial insomnia (FFI)]. [1] Several months into the disease course, the patient stops sleeping altogether. By this stage, they have started to lose many basic brain and body functions. [2] No drugs that we currently have will help the patient sleep. [3] After twelve to eighteen months of no sleep, the patient will die. Though exceedingly rare, [4] this disorder asserts that a lack of sleep can kill a human being. [numeration mine]

Statement [1]:

Several months into the disease course, the patient stops sleeping altogether.

This is false. Here’s a description of a case of FFI (a) from the case report paper I referenced in Section 3 (a): Schenkein J, Montagna P. Self-management of fatal familial insomnia. Part 2: case report. Medscape General Medicine. 2006;8(3):66.

Until roughly the 23rd month, DF’s sleep patterns showed a definite cycle, which may have reflected his rotating schedule of the various medications. The first night, he slept well; the second night, less well; and the third, still less, followed by 1–2 sleepless nights. Then the cycle repeated.

Statement [2]:

No drugs that we currently have will help the patient sleep.

This is false. From the same paper:

Gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) was administered during the last month of DF’s life. … According to his caretaker, GHB resulted in sleep within 30 minutes of administration, but did not last long enough for DF to feel rested.

Finally, statement [3] is also false. In case you suspect that he was only writing about the typical course of the disease when writing “After twelve to eighteen months of no sleep, the patient will die”, in Chapter 12, Walker clarifies:

Every patient diagnosed with the disorder [FFI] has died within ten months, some sooner"

Setting aside the question of how all the patients who died within ten months of diagnosis were able to get “twelve to eighteen months of no sleep” – if, as Walker writes, the patient loses sleep several months into the disease course and dies within eighteen months of no sleep, then life expectancy from the onset of the disease is no more than two years. However, for example, this paper (doi) finds that: Montagna P, Cortelli P, Avoni P, Tinuper P, Plazzi G, Gallassi R, Portaluppi F, Julien J, Vital C, Delisle MB, Gambetti P. Clinical features of fatal familial insomnia: phenotypic variability in relation to a polymorphism at codon 129 of the prion protein gene. Brain Pathology. 1998 Jul;8(3):515-20.

Detailed analysis of 14 cases from 5 unrelated families showed that patients ran either a short (9.1+ 1.1 months) or a prolonged (30.8 + 21.3 months) clinical course according to whether they were homozygote met/met or heterozygote met/val at codon 129.

See discussion of statement [4] in Section 3.

Basically everything in Walker’s description of the disease is wrong, aside from the fact that people suffering from it die eventually.

Appendix: an email from a UK-based sleep scientist

He [Walker] has been frustrating to many in the sleep field for years—talks showing bar graphs without any error bars, clear misunderstandings of p-values, etc. Check out this doozy from a review back in 2005:

In Table 1, he shows a series of studies with various p-values, then claims that the “The combined probability of 10^-15 reflects the likelihood of all six studies providing such low probabilities for the null hypothesis.” How did he generate such a small p-value? It appears he multiplied the numbers from the studies together—but that is by no means a correct methodology! It doesn’t take much knowledge of p-values to realize the absurdity of this: no one would claim that 6 studies with a p-value of 0.5 for a phenomenon would nevertheless be convincing evidence of a real effect (0.5^6=0.015)!

Just to add to your pile of errors in the Why We Sleep book, in Chapter 12 there is a confused section when he talks about narcolepsy and says, “Medically, narcolepsy is considered to be a neurological disorder, meaning that its origins are within the central nervous system, specifically the brain. The condition usually emerges between ages ten and twenty years. There is some genetic basis to narcolepsy, but it is not inherited. Instead, the genetic cause appears to be a mutation, so the disorder is not passed from parent to child. However, gene mutations, at least as we currently understand them in the context of this disorder, do not explain all incidences of narcolepsy.” Page 181.

His discussion of genetics here is very confused. If there were a genetic cause, it would be inherited—and in fact there are rare cases of narcolepsy due directly to mutations in the signalling cascades involved in narcolepsy (Hypocretin/orexin signalling). For example, an examples was reported in this study: https://med.stanford.edu/content/dam/sm/narcolepsy/documents/autopsy/naturemed6.pdf But this is very, very rare.

What he seems to be confusing is the data showing that a certain fairly common human HLA variation is strongly associated with developing narcolepsy—but since most people who have this variation do not get narcolepsy, the HLA variant alone cannot be causal for narcolepsy by itself. E.g. these studies: Tafti M, Hor H, Dauvilliers Y, et al. DQB1 locus alone explains most of the risk and protection in narcolepsy with cataplexy in Europe. Sleep. 2014;37:19–25.

Hor H, Kutalik Z, Dauvilliers Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies new HLA class II haplotypes strongly protective against narcolepsy. Nat Genet. 2010;42:786–9.

It is utterly nonsensical to say, “The genetic cause appears to be a mutation, so the disorder is not passed from parent to child.” It is not usually passed from parent to child, true, but that is not because of the genetic cause being a mutation, which WOULD make it inherited. That common HLA variant certainly IS passed from parent to child. But since the HLA locus is not “the genetic cause”, narcolepsy is not (usually) inheritable.

Appendix

Possible origin of the “sleeplessness epidemic” thing

Between late 2010/early 2011 and August/September 2015 [1 (a), 2 (a), 3 (a), 4 (a)], CDC had a page on its site titled “Insufficient Sleep Is a Public Health Epidemic”. More than 2 years before Why We Sleep was published, the page changed the word “epidemic” to “problem”, so that its title became “Insufficient Sleep Is a Public Health Problem”.

A charitable interpretation of this would be that Walker simply misremembered the organization (and added the “industrialized nations” bit). Even this interpretation suffers from

- the fact that the documentary he used as a source never mentions CDC or the WHO and never mentions any sleeplessness epidemics

- the fact that CDC itself changed the wording from “epidemic” to “problem” more than 2 years prior to the book’s publication, indicating that they no longer believed in the presence of an “insufficient sleep epidemic”

- the fact that, just a page earlier, Walker attributes to the WHO another thing it never declared (see Section 5)

- in a video published in 2019 by Penguin Books UK, he says “it’s very clear right now that there is a global sleep loss epidemic and I wish those were my own words but they are the words of the World Health Organization”

Walker talked about this a bit in an interview to DailyGood (a) a few months before the book was published (h/t Ellen). Note whether he actually answers the interviewer’s question:

Aryae: You talk about the global sleepless epidemic as the greatest public health challenge that we are now facing, and hearing what you are now saying, it makes a lot of sense. Before the call, I was curious and Googled public health challenges and I got all kinds of lists.*Here is one from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that was published in March 2017. They have on the list alcohol-related harms, food safety, healthcare-associated infections, heart disease/strokes, HIV, motor vehicle injuries, nutrition, physical activity and obesity, prescription drug overdose, teen pregnancy, and tobacco use. They do not have sleep on their list. So what do you say about that discrepancy?

Matt: What is fascinating is that almost every one of those large public health concerns is directly related to insufficient sleep. So, for example, we know that insufficient sleep is tied to high rates of cardiovascular disease, the calcification of the coronary arteries, hypertension, and stroke. We also know that sleep loss is causally related to obesity. Sleeplessness has a profound impact on your immune health and in fact you can go to so many of the classic immune disorders even the common cold. People who get six hours of sleep or less are between 50% or 60% more likely to catch a cold than those who sleep more.

Cancer is now strongly related to insufficient sleep. That includes cancer of the bowel, cancer of the prostate, and cancer of the breast. So much so that in fact the World Health Organization (WHO) recently classified any form of nighttime shift work as a probable carcinogen. Set jobs that disrupt your sleep wake rhythm are cancer-inducing, that is how strong the evidence is right now.

We now know that drowsy driving causes more accidents on our roads then either drugs or alcohol combined. And yet we spend a fraction of 1% of our public health policy budget on educating people about the dangers of insufficient sleep.

Risk-and-reward behaviors are intimately tied to insufficient sleep, from risky behavior to drug addiction and drug-taking and teenage pregnancy. We’ve done a lot of work in this area, too, particularly on adolescent youth. You shorten their sleep; they become much more risk-taking and sensation-seeking. They engage in behaviors that are high-risk behaviors.

Every one of the conditions on that list has a link to insufficient sleep! So why sleep is not on that list is so desperately sad and striking to me. That is why people like me needed to become much better sleep ambassadors. We need to go to places like Capitol Hill. We need not just go there waving our hands saying look at this problem. We need to come up with 21st century new visions of solutions. And that is one of the things that I speak about in the forthcoming book. And is one of the things that I am trying to now push very hard with a number of quick advocacy policies. We need to change society for the better. We need to reorient and prioritize!

“What You Can Learn From Hunter-Gatherers’ Sleeping Patterns”

The Atlantic (a):

Here’s the story that people like to tell about the way we sleep: Back in the day, we got more of it. Our eyes would shut when it got dark. We’d wake up for a few hours during the night instead of snoozing for a single long block. And we’d nap during the day.

Then—minor key!—modernity ruined everything. Our busy working lives put an end to afternoon naps, while lightbulbs, TV screens, and smartphones shortened our natural slumber and made it more continuous.

All of this is wrong, according to Jerome Siegel at the University of California, Los Angeles. Much like the Paleo diet, it’s based on unsubstantiated assumptions about how humans used to live.

Siegel’s team has shown that people who live traditional lifestyles in Namibia, Tanzania, and Bolivia don’t fit with any of these common notions about pre-industrial dozing. “People like to complain that modern life is ruining sleep, but they’re just saying: Kids today!” says Siegel. “It’s a perennial complaint but you need data to know if it’s true.”

Such data have been hard to come by because the devices that we use to measure and record sleep have only been invented in the last 50 years, and those that do so without disturbing the sleepers are just a decade old. So, there’s no baseline for how long people used to sleep before electric lights. Absent that baseline, Siegel’s team did the next best thing: They studied people who live traditional lifestyles, including Hadza and San hunter-gatherers from Tanzania and Nambia respectively, and Tsimane hunter-farmers from Bolivia.

The team asked 94 people from these groups to wear Actiwatch-2 devices, which automatically recorded their activity and ambient-light levels. The data revealed that these groups all sleep for nightly blocks of 6.9 and 8.5 hours, and they spend at least 5.7 to 7.1 hours of those soundly asleep. That’s no more than what Westerners who have worn the same watches get; if anything, it’s slightly less.

They don’t go to sleep when it gets dark, either. Instead, they nod off between 2 and 3 hours after sunset, well after it becomes pitch-black. And they napped infrequently: The team scored “naps” as periods of daytime inactivity that lasted for at least 15 minutes, and based on these lenient criteria, the volunteers “napped” on just 7 percent of winter days and 22 percent of summer ones.

Most sleep does not serve a vital function: Evidence from Drosophila melanogaster

No relation to Walker’s book, but this paper (a): Geissmann Q, Beckwith EJ, Gilestro GF. Most sleep does not serve a vital function: Evidence from Drosophila melanogaster. Science Advances. 2019 Feb 1;5(2):eaau9253. is really fun:

Sleep appears to be a universally conserved phenomenon among the animal kingdom, but whether this notable evolutionary conservation underlies a basic vital function is still an open question. Using a machine learning–based video-tracking technology, we conducted a detailed high-throughput analysis of sleep in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster, coupled with a lifelong chronic and specific sleep restriction. Our results show that some wild-type flies are virtually sleepless in baseline conditions and that complete, forced sleep restriction is not necessarily a lethal treatment in wild-type D. melanogaster. We also show that circadian drive, and not homeostatic regulation, is the main contributor to sleep pressure in flies. These results offer a new perspective on the biological role of sleep in Drosophila and, potentially, in other species.

No, not every living creature generates a circadian rhythm

In the third paragraph of Chapter 2, Walker writes:

[E]very living creature on the planet with a life span of more than several days generates this natural [circadian] cycle

This is false. Brewer’s yeast (S. cerevisiae):

- live for more than 20 days (Figure 1 in this paper (a) Fabrizio P, Longo VD. The chronological life span of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell. 2003 Apr;2(2):73-81. )

- do not generate a circadian cycle [1 (a) Merrow M, Raven M. Finding time: A daily clock in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(9):1671–2. , 2 (a) Wildenberg GA, Murray AW. Evolving a 24-hr oscillator in budding yeast. Elife. 2014 Nov 10;3:e04875. ]

There are two ways to view this error:

- this is a minor point and most people would think that he only means animals anyway

- this is a minor but fundamental point. Walker misstates basic facts about sleep and misleads readers about them. Counterexamples to “universal” phenomena are important

Circadian rhythm in general is overrated [1 (a) Hazlerigg DG, Tyler NJ. Activity patterns in mammals: Circadian dominance challenged. PLSS Biology. 2019 Jul 15;17(7):e3000360. , 2 (doi) Bloch G, Barnes BM, Gerkema MP, Helm B. Animal activity around the clock with no overt circadian rhythms: patterns, mechanisms and adaptive value. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2013 Aug 22;280(1765):20130019. ].

Extended quote about the dangers of lack sleep from Chapter 1

I doubt you are surprised by this fact, but you may be surprised by the consequences. Routinely sleeping less than six or seven hours a night demolishes your immune system, more than doubling your risk of cancer. Insufficient sleep is a key lifestyle factor determining whether or not you will develop Alzheimer’s disease. Inadequate sleep—even moderate reductions for just one week—disrupts blood sugar levels so profoundly that you would be classified as pre-diabetic. Short sleeping increases the likelihood of your coronary arteries becoming blocked and brittle, setting you on a path toward cardiovascular disease, stroke, and congestive heart failure. Fitting Charlotte Brontë’s prophetic wisdom that “a ruffled mind makes a restless pillow,” sleep disruption further contributes to all major psychiatric conditions, including depression, anxiety, and suicidality.

Perhaps you have also noticed a desire to eat more when you’re tired? This is no coincidence. Too little sleep swells concentrations of a hormone that makes you feel hungry while suppressing a companion hormone that otherwise signals food satisfaction. Despite being full, you still want to eat more. It’s a proven recipe for weight gain in sleep-deficient adults and children alike. Worse, should you attempt to diet but don’t get enough sleep while doing so, it is futile, since most of the weight you lose will come from lean body mass, not fat.

Add the above health consequences up, and a proven link becomes easier to accept: the shorter your sleep, the shorter your life span.

The full discussion of sleep deprivation therapy from Chapter 7